|

|

- Search

| Healthc Inform Res > Volume 27(3); 2021 > Article |

|

Abstract

Objectives

Along with the exponentially-growing data produced and accumulated every day through mobile platforms, social networking services, the Internet, and other media, information is becoming increasingly important as a strategic resource. This report presents specific and clear directions and suggests empirical project plans regarding innovations in regional health information systems to promote the utilization of medical information.

Methods

We reviewed and examined documents about global trends and examples of regional health information systems. The problems and solutions of health information utilization and regional health information systems in Korea were analyzed.

Results

This study presented examples of the establishment of health information systems, problems in the use of local healthcare information, and an empirical project for improvement.

Conclusions

The results of this study imply the need for long-term and systematic approaches for the use of medical information and the establishment of a local healthcare information system, along with implementation plans. As a first step, it is imperative to clarify the goal of building a medical information system, the information that must be provided to build the system, and the data that should be collected to provide such information, while moving away from the mentality of focusing on technology-oriented medical information services. In addition, it is necessary to consider information governance, data-based service development, and the medical innovation framework, which are ways to efficiently manage, utilize, and systemize the data to be collected.

The current trends in the medical services environment are shifting from treatment and hospitals to prevention and consumers, in line with a growing interest in smart healthcare using medical information with the ongoing Fourth Industrial Revolution. Along with the exponentially-growing data produced and accumulated every day through mobile platforms, social networking services, the internet, and other media, information is becoming increasingly important as a strategic resource. In addition to this trend, the establishment of socio-economic and environmental factors as determinants of health has led to increasing demand for new regional health information systems for community-based care services.

A regional health information system is defined as a multi-stakeholder organization working together to connect healthcare communities with the goal of improving quality of care, the health of individuals, and the efficiency of public health systems [1–3]. Regional collaborations, which are termed regional health information organizations or health information exchange organizations, are multi-stakeholder organizations created to facilitate a health information exchange (HIE) [4]. The relevant stakeholders may include hospitals, nursing facilities, clinic centers, private physicians’ offices, pharmacies, laboratories, radiology facilities, health departments, and possibly patients themselves [5,6].

In an effort to build an ecosystem for innovations, the South Korean government according to global trends is promoting a “Digital New Deal” project centered on a Data Dam project, intelligent government, and smart medical care as three core national public policy tasks. This Digital New Deal is closely related to the use of medical information and health information systems.

This report presents specific and clear directions and suggests empirical project plans regarding the use of medical information in the healthcare sector and a regional health information system for the success of the Digital New Deal project, with the goal of improving structural imbalances in the sector and successfully transitioning to the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Along with the concept of the “Health Field” suggested by Lalonde’s report [7], a World Health Organization report stated that the determinants of health include environmental factors, including socio-economic and national factors, in addition to individual factors [8]. Based on this definition, the perception became more common that states and communities, in addition to individuals, should also be responsible for health, and this perception has led to a need for community-centered healthcare systems. Health management should be approached from the perspective of the healthcare ecosystem including the local community and the national system, instead of an individual-centered approach, and a healthcare information system, which is sub-system of healthcare system, should also be established based on an ecological approach.

Since it is difficult to manage residents’ health conditions only at local healthcare institutions, a healthcare ecosystem in which healthcare institutions and other relevant agencies systematically cooperate in managing a regional health system is essential. Thus, hospitals and clinics, health institutions, nursing homes, emergency medical institutions, community centers, the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS), social welfare centers, care centers, and local governments should build an ecosystem of healthcare services led by regional community medical institutions.

The healthcare information ecosystem refers to an information ecosystem in which the health information of each institution within the healthcare ecosystem is systematically and organically linked, enabling various types of healthcare data to be integrated for efficient use. The data managed within the healthcare information ecosystem deal not only with diseases, but residents’ level of well-being and functional status. The data also encompass socio-economic aspects that affect the above-mentioned factors [9].

Within this healthcare information system, various information requirements from different stakeholders co-exist. Individuals are responsible for their own health, and healthcare buyers need reliable information when they become consumers and advocates. Healthcare providers guide medical decisions for patients, and request the information necessary to coordinate and manage patient treatment. Insurers want information for healthcare planning, pricing and reimbursements, quality and cost monitoring, and effective health and disease management services, while community healthcare institutions require information to protect and improve the health of the residents within their communities. Researchers could also use information to develop new and improved drugs, medical devices, and biological agents and to evaluate their efficacy [10].

Currently, global trends in the use of healthcare information are advancing toward addressing various medical information requirements from a wide range of organizations and stakeholders within the healthcare ecosystem. Nevertheless, it is difficult to satisfy all those needs due to conflicting interests. Therefore, proper governance should be put in place for healthcare information management.

The Indiana Network for Patient Care (INPC) is a regional health information infrastructure that integrates medical data from five major hospital systems (15 individual hospitals), county- and state-level public health departments, Indiana Medicaid, and RxHub. Providing patient care services since the mid-1990s, the INPC verifies patients’ identities using a real-time clinical data stream. More than 80 hospitals, numerous outpatient clinics, laboratory systems, and public health institutions are using the data accumulated over 30 years to provide healthcare services for residents, to inform clinical decision-making, and to support high-quality reporting and research. This largest-ever HIE platform connecting more than 35,000 healthcare providers in 17 states provides patients with relevant information at any time and any place. Hospitals, doctors, clinics, healthcare institutions, clinical laboratory, radiography centers, local governments, medical societies and associations, and the government department in charge of economic development also participate in the INPC.

The Wakashio Medical Network is a regional medical service network system for safe and reliable medical services and treatment. Through the system, real-time health information can be shared through a medical network connecting regional healthcare institutions such as public health centers, major hospitals, and pharmacies. Under this system, medical specialists can provide healthcare services at regional medical institutions through an improved chronic disease management system. It also provides customized medical services utilizing the latest technologies, such as a gene therapy support system [13].

This is an integrated medical data sharing system where patients’ medical information and clinical data from medical institutions are controlled and shared through Electronic Medical Records (EMRs) at Kakogawa General Health Center. This system aims to ensure that all residents can equally receive optimal medical care at any time and any place. As it is linked with the long-term care networks of the Care Net System, medical providers can also participate in this service. Under the system, individual healthcare information is recorded on an IC card, and personal health data are stored in a common local database of the system [14].

As of 2017, the penetration rate of EMRs in Korea was 77.8% for all medical institutions and 91.4% for hospitals and higher level institutions [15]. However, the EMR data are not being used properly and efficiently for the following reasons:

First, the standardization of terminology for EMR data is an issue that makes it difficult to share EMR data among medical institutions. Second, since about 80% of EMRs are unstructured data such as text, images, and videos [15], it is inherently difficult to efficiently utilize the data. Third, as exemplified by the phenomenon of “up-coding” to avoid medical fee reduction in health insurance screening, which is tarnishing the reliability of the overall diagnostic data (which is also the most essential part of EMRs), the quality of EMR data is generally low and other medical data are also not properly managed. This data reliability issue hampers the effective and efficient use of EMR data.

Currently, medical institutions in Korea have built clinical data warehouses and common data models (CDMs) for their own use. However, these data have the same limitations as EMRs, as EMRs serve as the data source. This means that there are many problems with the data items, although the number of items to be referenced is relatively large. Aside from the issues related to data standards, it is also difficult to utilize unstructured data, which account for about 80% of all data items. Since unstructured data are not included as variables, it is cumbersome to use unstructured data for the purposes of medical information sharing, clinical decision-making, and research. The utility of CDM data is also limited as enormous efforts are needed to load data by mapping the Korean Classification of Diseases (KCD) codes to each hospital’s own codes, not to mention the possible data loss occurring in the process.

In addition, since the qualitative level of EMR-based healthcare big data is low, it is difficult to expect excellent performance from artificial intelligence (AI) analyses using it. Meanwhile, many new studies and applications are being carried out and developed at a hospital level, such as medical AI applications based on partial data (e.g., imaging data such as computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging). Trials of AI-based prediction models based on these data have shown that although the modeling performance was excellent, on-site application faces many issues due in part to poor quality control of the image data at the level of medical institutions.

Meanwhile, data required for regional healthcare projects are not collected in a systematic and comprehensive manner. Although there is an integrated information system for healthcare institutions, it merely supports computerized systems for local healthcare institutions or provides administrative-level data, failing to serve as a sufficient data pool supporting regional healthcare projects or relevant policy decisions. Since the poor quality and quantity of data make it difficult to properly support care services or other regional healthcare projects, a paradigm shift towards a new regional medical information system is necessary.

Currently, the paradigm in the medical services sector is moving towards more value-based medical services. “Value” can generally be defined as “relative worth,” “utility,” or “importance,” but different stakeholders such as medical service providers, medical consumers, and policy-makers have their own definitions of the concept of value. For medical services providers, value-based medical services would mean a healthcare system in which health-related risks are minimized with maximum benefits for patients, resulting in higher profits made possible by effective care with lower costs. For medical service consumers, value-based healthcare means a lower possibility of long-term hospitalization and a decreased recurrence rate, while policy-makers would view it as optimal cost performance in terms of patients’ health conditions. Therefore, the current medical information utility environment should be improved to accommodate diverse views on the value of healthcare [15].

We are living in an era where information is considered an asset. Based on this perspective, therefore, it is necessary to employ an enterprise information management (EIM) system for the efficient management of medical data. EIM refers to a series of management functions encompassing data and the life cycle of information. To guarantee the value of information assets, organization-wide information management functions as well as clear structures, policies, processes, technology, and controls are required. EIM is an infrastructure and process that guarantees reliable and actionable information [11].

To meet the needs of the times, the operation of the current regional healthcare information system focusing on ordinary work at public health centers, should further be expanded to support community care services. To make this happen, a new regional healthcare information system based on community health records (CHRs) should be established [16].

Currently, the regional health information system used by public health centers mainly includes data gathered for administrative convenience in project management, and as such it is difficult from a practical standpoint to provide various medical-related services using the regional health information system. There should be an information system that can utilize integrated health data of residents to provide community care services. Unfortunately, only the regional health information system for public health centers is in place, covering public health center project data and public health project management.

CHRs are a new form of electronic health records for residents designed to support community care. CHRs include personal data and regional community health index data. From an individual’s perspective, CHRs are integrated medical records collected from different institutions within the community for qualified medical service providers. From a more collective perspective, CHRs are medical records taking stock of each community’s health data, including social, physical, and lifestyle determinants of health. CHRs are health information about individuals and regions (groups) in terms of social, physical, and lifestyle factors affecting their health, as well as the health records of residents established primarily for healthcare providers [16].

In addition, as a customized regional healthcare services project based on spatial decision-making incorporating geographic information system (GIS) data, a practitioner (primary medical institution) and vendor-oriented, cloud-based regional health information system and an integrated community care service portal/app or information sharing system can be proposed as a demonstration project to prepare and establish a regional health information system through the efficient use of medical information.

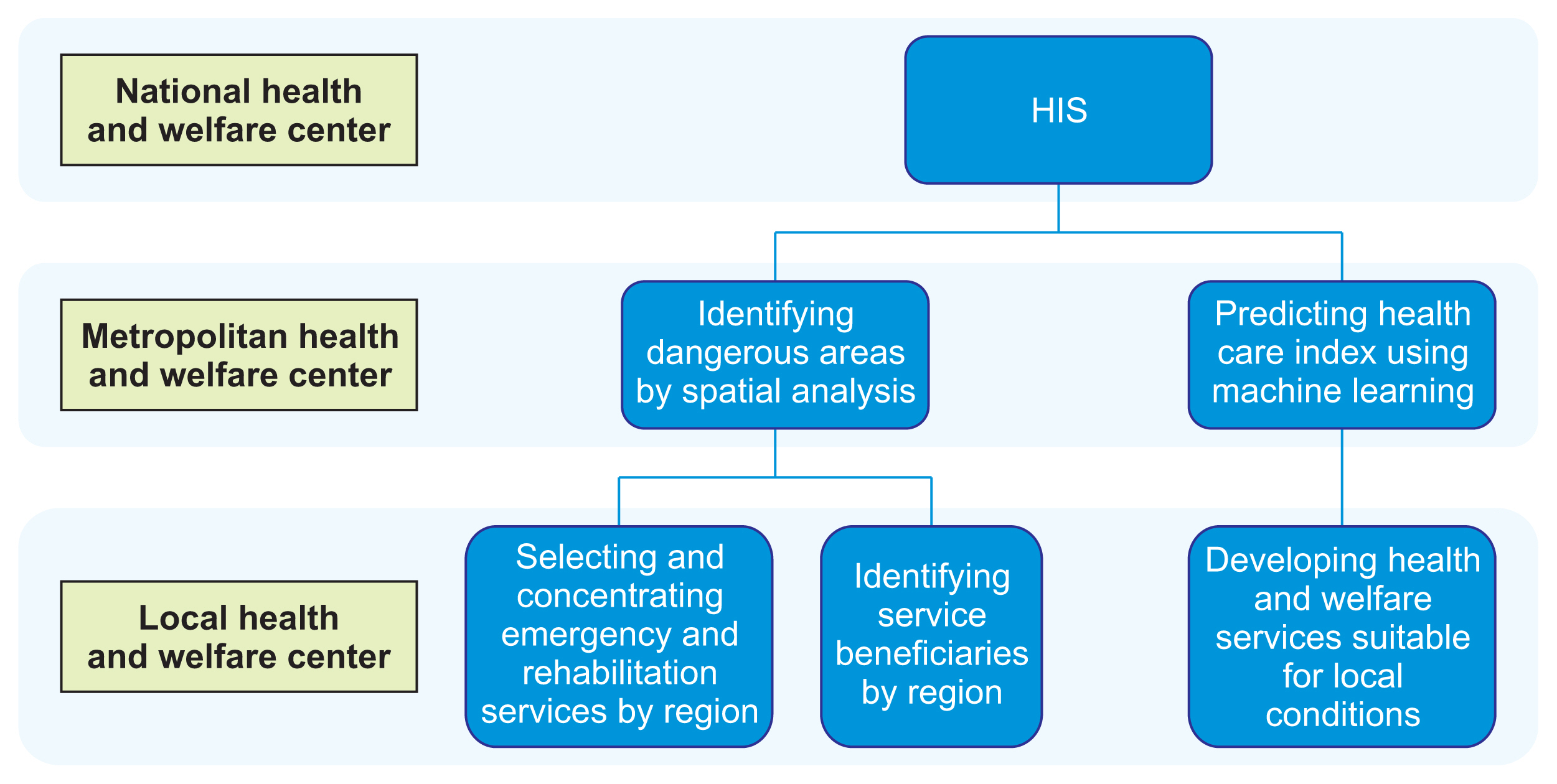

A customized regional healthcare services project based on spatial decision-making employing GIS would be a tailor-made regional health project utilizing regional health indicators and spatial analysis techniques that can grasp the characteristics of each community (Figure 1). In connection with centers at the level of metropolitan cities and local governments across the country, this project aims to establish an information management system that supports and implements health programs suitable for specific conditions. This program will allow the prediction of the scale of future health problems by region through spatial data mining, and therefore can facilitate the preparation of customized regional healthcare projects. This service model would enable the preemptive application of customized health projects for each region based on prediction data, advancing beyond current healthcare projects in which project plans are established using past indicators.

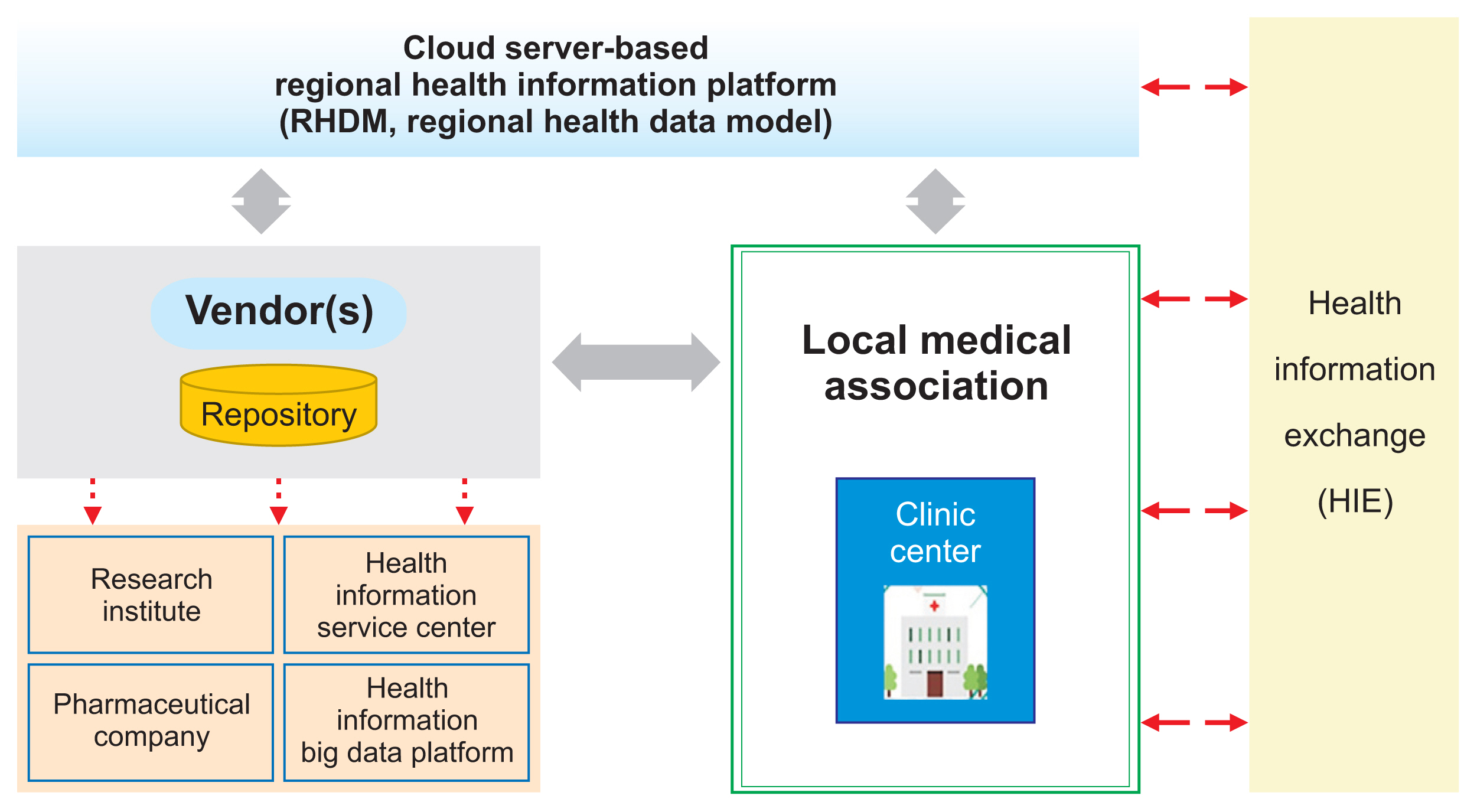

In a practitioner (primary medical institution) and vendor-oriented, cloud-based regional healthcare information system, the medical institutions within a community would be able to gather and analyze medical data following standard data items, formats, and codes. This is expected to be a system that can solve the problems of the limited use of healthcare big data platforms built around Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA), National Health Insurance Services (NHIS), National Cancer Center (NCC), and the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA). Led by the local community of medical practitioners, this model is established to develop a cloud-based community healthcare information system model by signing contracts with vendors. The medical data collected from self-employed medical providers through this system can be used to build a platform for clinical research and medical information sharing. As such, this model demonstrates strong potential with high feasibility and utility (Figure 2).

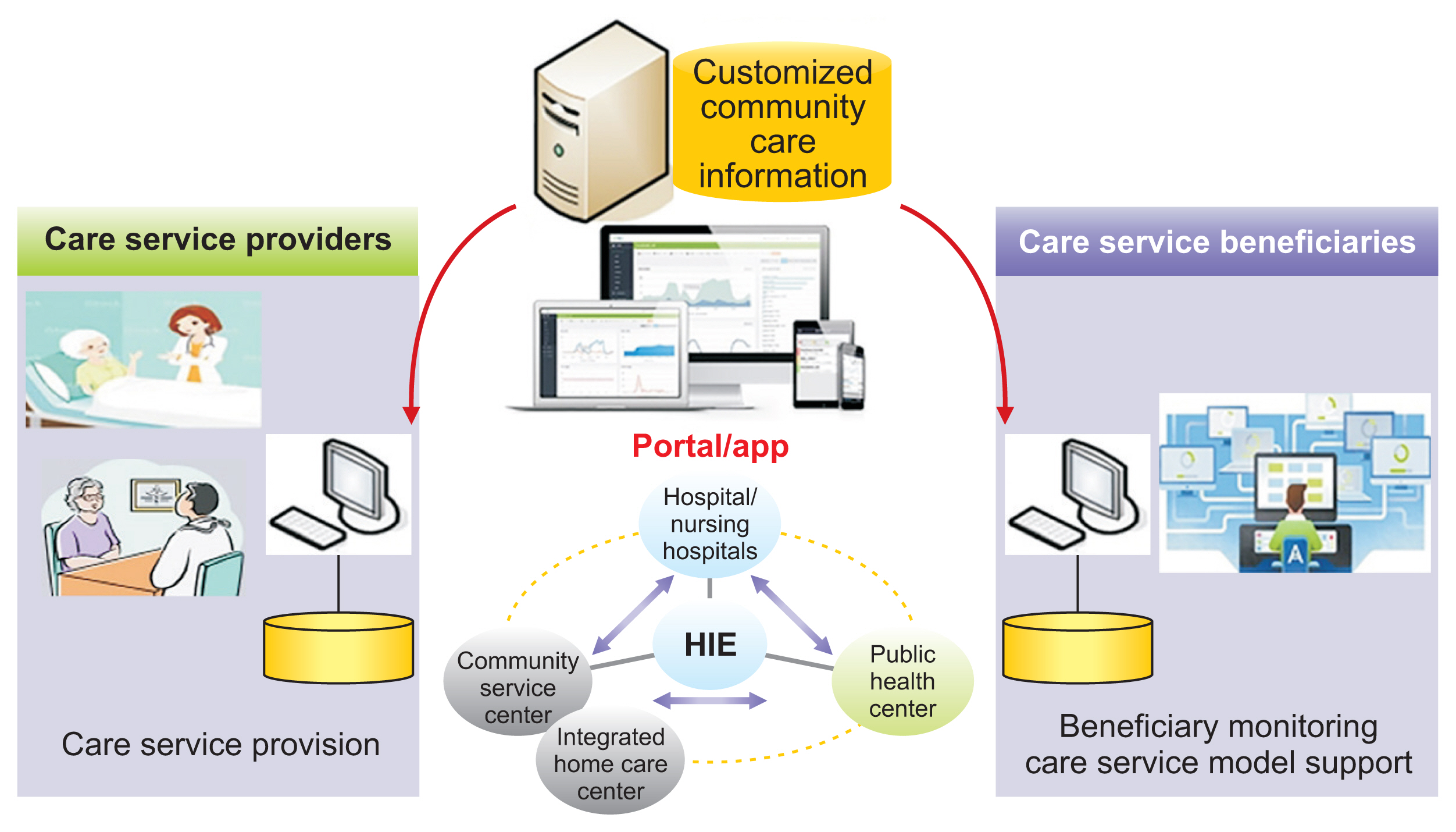

Demonstrative projects such as the development and application of an integrated community care service portal app or information sharing system are an information and communication technology–based service model for customized community care in which professionals from local medical institutions, social welfare centers, and public health centers participate. Currently, community-level management for the elderly who are treated at public facilities or who are discharged from medical institutions is divided across different medical care services and welfare sectors, and relevant information systems are also separately established at each institution [17].

Community care services provision has become more sophisticated, but it faces the issue of fragmented provision (service providers/beneficiaries) and technical inefficiency due to inappropriate usage of information and communication technologies. Currently, medical institutions’ medical records and discharged patient management system (home care, comprehensive elderly evaluation for discharged/re-hospitalized patients, discharge summary), public health center programs (local medical information system), and local healthcare and welfare services (home care - long-term care certificates, in-home elderly support programs, integrated basic care services for the elderly, etc.) are all operated separately [15]. There are many problems with service delivery, including poor information sharing about the beneficiaries among service providers, making it difficult to collect the information required to provide them with appropriate services in an integrated manner.

Therefore, it is necessary to develop an integrated community care service model in the form of a web portal for service providers based on relevant standards so that different entities can share information about beneficiaries, update details about the services provided, and provide timely and on-demand services to beneficiaries. This report proposes to establish such an integrated system in which service providers can freely access basic information of the beneficiaries, which could have only been collected through contact or in-person visits until now (Figure 3).

Today’s medical information and regional health information systems should be able to contribute to providing optimal healthcare services to the public and residents by reinforcing national and regional healthcare systems, going beyond merely providing the information needed to carry out given projects. To this end, it is imperative to first clarify the goal of building a medical information system, the information that must be provided to build the system, and the data that should be collected to provide such information, while moving away from the mentality of focusing on technology-oriented medical information services. In addition, it is necessary to consider information governance, data-based service development, and medical innovation framework, which are ways to efficiently manage, utilize, and systemize the data to be collected. In response to the needs of the times, the United States developed a national data strategy in 2020 for mobilizing national healthcare information capabilities [18]. As such, we should also take a long-term and systematic approach by preparing a health data strategy related to the use of medical information and establishment of a local healthcare information system, along with actionable implementation plans. It is also necessary to implement the project after clearly establishing plans for a service- and data-oriented information system, away from a systems-oriented approach.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea and supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (No. NRF-2018R1D1A1B0705000913, Hyejin Park).

References

1. Maenpaa T, Suominen T, Asikainen P, Maass M, Rostila I. The outcomes of regional healthcare information systems in health care: a review of the research literature. Int J Med Inform 2009;78(11):757-71.

2. Overhage JM, Evans L, Marchibroda J. Communities’ readiness for health information exchange: the National Landscape in 2004. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2005;12(2):107-12.

3. Dykes P, Bakken S. National and regional health information infrastructures: making use of information technology to promote access to evidence. Stud Health Technol Inform 2004;107(Pt 2):1187-91.

4. What is Health Information Exchange? [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): American College of Rheumatology; 2010 [cited at 2021 Apr 23]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regional_Health_Information_Organization

5. Marchibroda JM. Health information exchange policy and evaluation. J Biomed Inform 2007;40(6 Suppl):S11-6.

6. Shapiro JS, Kannry J, Lipton M, Goldberg E, Conocenti P, Stuard S, et al. Approaches to patient health information exchange and their impact on emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med 2006;48(4):426-32.

7. Lalonde M. A new perspective on the health of Canadians [Internet]. Ottawa, Canada: Minister of National Health and Welfare; 1974 [cited at 2021 Apr 23]. Available from: https://nccdh.ca/resources/entry/new-perspective-on-the-health-of-canadians

8. World Health Organization. The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; c2021 [cited at 2021 Apr 23]. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/index.html

9. Grossmann C, Powers B, Michael McGinnis J. Digital infrastructure for the learning health system: the foundation for continuous improvement in health and health care: workshop series summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2011.

10. Kloss L. Implementing health information governance: lessons from the field. Chicago (IL): AHIMA Press; 2015.

12. Magnuson JA, Dixon BE. Public health informatics and information systems. 3rd ed. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2020.

13. Lee KS, Lee SK, Lee MS, Lee JJ, Ryu SY, Kim HS, et al. Research for improvement of public health information system. Sejong, Korea: Ministry of Health and Welfare, Konkuk University; 2016.

14. Shin JW. The challenge of improving the collection and use of electronic medical records. Health Welf Policy Forum 2018;(262):29-38.

15. Brown MM, Luo B, Brown HC, Brown GC. Comparative effectiveness: its role in the healthcare system. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2009;20(3):188-94.

16. King RJ, Garrett N, Kriseman J, Crum M, Rafalski EM, Sweat D, et al. A community health record: improving health through multisector collaboration, information sharing, and technology. Prev Chronic Dis 2016;13:E122.

17. Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism. Integrated community care services (Community Care) [Internet]. Sejong, Korea: Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism; 2018 [cited at 2021 Apr 23]. Available from: https://www.korea.kr/special/policyCurationView.do?newsId=148866645

18. Federal Data Strategy. 2020 Action Plan [Internet]. Washington (DC): Federal Data Strategy; 2020 [cited at 2021 Apr 23]. Available from: https://strategy.data.gov/action-plan/

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

- Related articles in Healthc Inform Res

-

Development of Occupation Health Information System based on the Internet1997 December;3(2)