|

|

- Search

| Healthc Inform Res > Volume 28(3); 2022 > Article |

|

Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to analyze the outcomes of the Comprehensive Health and Social Need Assessment (CHSNA) system, which identifies community residents’ health and social needs, and to link these needs with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF).

Methods

Adult community residents in a metropolitan city in Korea were recruited. They were asked to assess their health and social needs via the CHSNA system, which was integrated into an online community-care platform. Three assessment steps (basic health assessment, needs for activities of daily living, and in-depth health assessment) associated with five ICF components were used to evaluate physical health impairment, difficulties in activities and participation, and environmental problems. The final list of health and social needs was systematically linked to the domains and categories of the ICF. Only data from participants who completed all three assessment steps were included.

Results

Wide ranges of impairments and difficulties regarding the daily living activities, physical health, and environmental status of the community were recorded from 190 people who completed assessments of their health and social needs by the CHSNA system. These participants reported various health and social needs for their community life; common needs corresponded to the ICF components of body functions and activities/participation.

Conclusions

The ICF may be suitable for determining the health-related problems and needs of the general population. Possible improvements to the present system include providing support for completing all assessment steps and developing an ICF core set for an enhanced understanding of health and social needs.

The growth of the aging population, as well as the increasing burden of multiple long-term conditions, has placed significant pressure on the health and social care system in many countries. Governments must respond to these changes by making appropriate adjustments to policies and care models. Various models have been developed that share the concept of integration [1]. Healthcare systems, social organizations, and communities could be integrated to provide multiple services for a variety of population groups in many settings. Evidence has shown that the integration of health and social care services improved quality of care and access to care, increased patient satisfaction, and reduced unmet health and social care needs [2]. While early models of integrated care tended to focus on single case management, more recently they have shifted toward a broader approach, with the aim of enhancing population health [3]. In recent years, the community care model in Korea has also promoted integrated care by supporting community residents to remain living independently in their own communities for longer by providing needs-based services and enhancing social engagement [4].

Providing care and support for preferences and personal goals, in addition to interventions centered on the needs of individuals and communities, is critical for the delivery of integrated care services [5]. In Korea, community health surveys have shown that between 11.0% and 17.4% of individuals continue to experience unmet healthcare needs [6,7]. Although unmet healthcare needs gradually decreased through expansions of National Health Insurance coverage, a proportion of Koreans continued to be unable to receive needed healthcare services due to economic hardship, with relevant factors including the unacceptability of available services and inconvenient transportation [7,8]. Unmet needs are a critical component that must be resolved to fulfill the wishes of patients and their caregivers, as well as for care providers to carry out their responsibilities [9]. Therefore, identifying the needs of care recipients is an important task that poses a key challenge for care providers for the effective provision of care and support to the population [9].

Widely used needs assessment tools include the WHODAS 2.0 [10] for various target groups, as well as EASY-Care [11] and CANE [12] for older adults. Among a variety of developed tools, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (known as the ICF) can be used for “a comprehensive analysis of experiences and needs from the personal perspective,” to understand both the experience of health and functioning, and the individual’s needs [13]. The ICF was released by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2001 to provide a standard language for describing health, functioning, and disability [14]. It is a universal classification of health and health-related states that uses a systematic coding scheme consisting of five components: body functions, body structures, activities and participation, environmental factors, and personal factors.

Compared to other need assessment tools, the ICF has been used in a broader range of various disciplines, health-related conditions, and sectors [15]. Several standardized measures have also been developed using the ICF as a framework for assessing health-related states and/or disabilities among, for example, elderly people [16], and adult patients after upper-extremity injuries [17]. However, most studies have used the ICF in clinical and rehabilitation contexts [18], and few studies have used the ICF in the general population in a community-based setting. Therefore, there is a need for more studies applying the ICF to community care to better understand the potential applications of the ICF for providing comprehensive information about health and health-related status in the general population [19].

In recognition of the need for a comprehensive analysis of the health and social needs of community residents, which play a fundamental role in care delivery, an online community-care platform was developed in 2019 [20]. That platform helped community residents to identify their health and social care needs through a personalized needs assessment and then provided a tailored care plan based on those needs. The ICF framework and codes were mapped in the Comprehensive Health and Social Need Assessment (CHSNA) system of the platform.

This study aimed to analyze the outcomes of the CHSNA, which identifies the health and social needs of community residents, and to link these needs with the ICF framework.

Community residents who were older than 19 years, living in a metropolitan city in Korea, and able to read and write were invited to use the platform. Adverts about the platform and information about the study were shared via the network of the City Social Welfare Center. People interested in the new community care platform were invited to use it. Data from individuals who completed the comprehensive health- and social-care assessment process (Figure 1) were exported from the platform and analyzed in the study.

The CHSNA system, which was based on the ICF framework, was integrated into the online community care platform [20]. A description of the development and content of CHSNA system has been published previously [21]. This system provided comprehensive information regarding the health and social needs of the participants, corresponding to the ICF’s components through three assessment steps (Figure 1), including a basic health assessment, a life and activity assessment, and an in-depth health assessment. Firstly, the participant created an account with a username and contact information (phone number or email address). They could access the platform with a hyperlink via a web browser on any device with an internet connection, such as a smartphone, tablet, or computer. They were encouraged to use the platform as needed for 2 months. People who were not able to use the platform by themselves could receive assistance from caregivers and social workers.

After activating an account in the community care platform, the user continued to the first assessment step to provide general information (e.g., demographic, household, and health behaviors) by filling in blank items. The system automatically moved to the next step after the user completed the items in each step.

Next, their needs for performing daily activities, including activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), and recreational and social participation activities, were assessed by short questions for which there were four possible responses: “not applicable,” “doing this activity well,” “want to do this activity better,” and “want to try to do this activity.” Participants who chose “want to do this activity better” or “want to try to do this activity” were grouped as having needs for that particular activity. The questions were based on a survey from the National Leisure Activity Survey of Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism [22].

The in-depth assessment step evaluated physical impairment, activities and participation, and environmental status. The WHO Multi-Country Survey Study on Health and Responsiveness [23] was adopted to assess impairment related to participants’ physical health. Items were evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (no difficulty) to 4 (extreme difficulty). The WHODAS 2.0 was used to evaluate the difficulty level of functional status with regard to activity and participation [10]. This instrument included six domains covering 36 items measured on the following 5-point scale: 1, no difficulty; 2, mild difficulty; 3, moderate difficulty; 4, severe difficulty; and 5, extreme difficulty. The overall score was transformed into a metric ranging from 0 (no disability) to 100 (full disability); higher scores indicate greater disability in terms of performing the tasks in activity and participation. We considered a disability score equal to or greater than 25 to indicate disability [10]. Environmental problems were assessed by binary yes-or-no questions about their housing and living environmental problems, where “yes” meant that participants had difficulties related to housing and their living environment, and “no” meant they had no such difficulties. The items included in the environmental problems component were adopted from the final report of a community health survey conducted by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency [24].

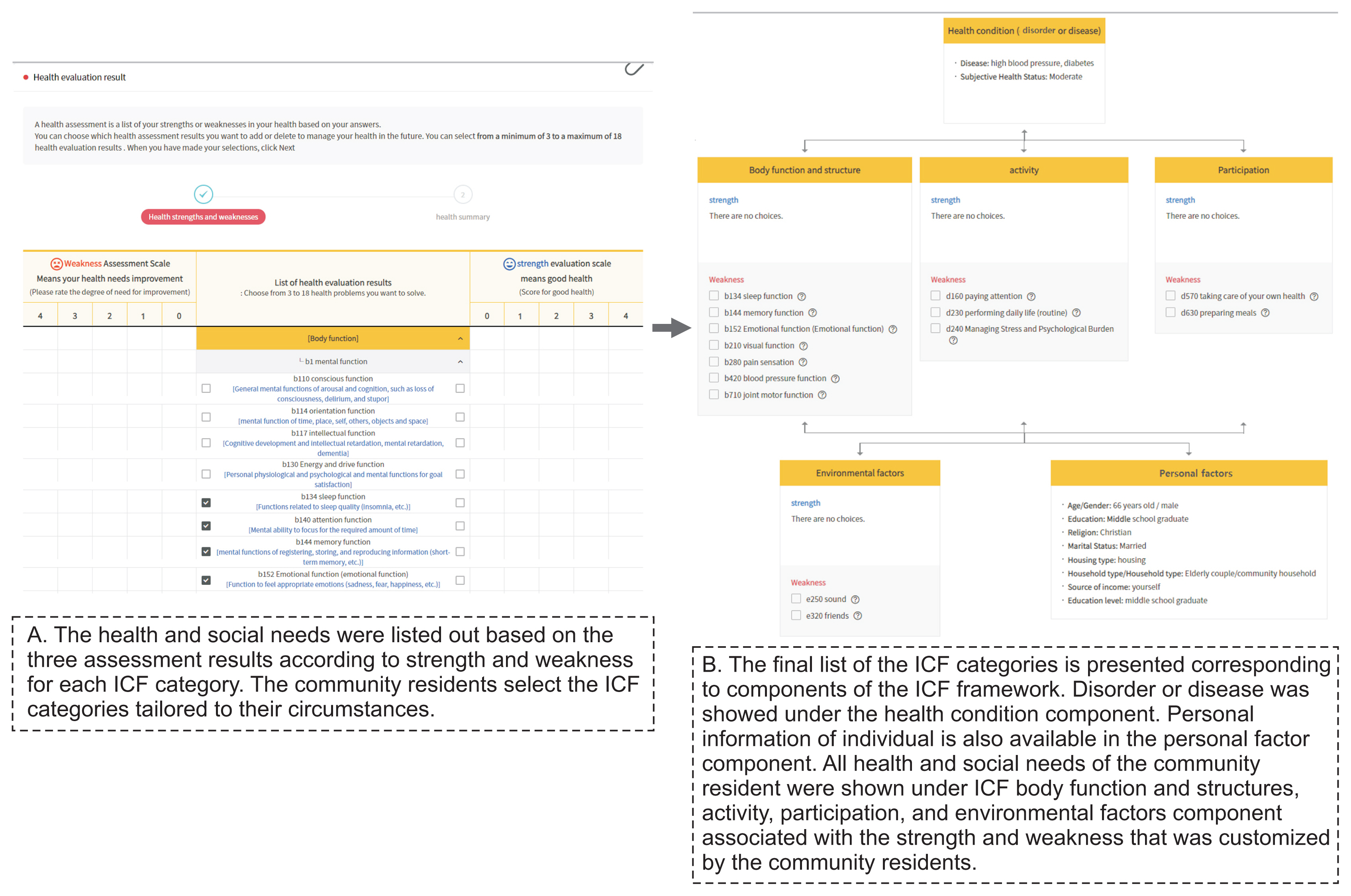

All items of the assessment steps were mapped to the ICF framework during the CHSNA system development; therefore, the profile indicating community residents’ functional status and health and social needs were illustrated using the corresponding ICF categories (Figure 2).

SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to perform analyses. The variables are described using mean ± standard deviation or frequency and percentage values. In this study, we linked and presented the health and social needs of participants to the ICF second-level domain; this linking rule was applied in a previous study to link health needs according to disability type using the ICF [25]. ICF categories that were reported by ≥5% of the participants were considered to be frequent health and social needs. There was no specific reference for the percentage threshold used to define frequent needs; however, we referred to a study reporting that the frequent ICF categories related to rehabilitation goals fluctuated from 5%–9% [26]. Therefore, we chose 5% as the cut-point for frequent needs in this study.

The study procedures were reviewed by the Chungnam National University Institutional Review Board (IRB), and the study was exempted from ethical approval by the IRB of the authors’ affiliated university (No. 201904-SB-037-01). Regarding informed consent, the participants were asked whether they agreed with the use of their data for research purposes when they logged onto the platform for the first time. No identified personal information of the users was included in this study.

Over the 2-month study period, 398 people created an account on the platform, of whom 283 filled in their basic information (step 1), 269 assessed their needs for activities of daily living (step 2), and 190 completed the three assessment steps of the CHSNA system. Data from those 190 users were analyzed. The number of users who completed each assessment step is shown in Figure 3, and the characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1. Data were collected from 190 community residents who were predominantly female (n = 159; 83.7%) and were aged 42.7 ± 17.8 years (range, 20–90 years). More than half of the participants were young adults aged between 19 and 44 years, while elderly participants accounted for 15.3%. Sixty-four (33.7%) participants reported that they had at least one chronic condition. The four most commonly self-reported chronic conditions were hypertension (17.4%), hyperlipidemia (9.5%), diabetes (5.8%), and arthritis (5.8%).

The number of people with needs in performing daily living activities was displayed as percentages. Infographics were created to represent 62 assessment items regarding needs for participating in daily living activities, which included five domains: ADL, IADL, indoor and outdoor recreational activities, and social participation activities (Figure 4). The most common need related to ADL was for self-care activities such as cooking to maintain independent care of oneself, which was reported by more than 20% of the participants. Among the IADL allowing an individual to live independently in the community, the most frequent needs were found for driving and managing money, which were reported by more than 15% of participants. The prevalence of the need to participate in social activities fluctuated between 5% and >25% of participants. Community residents had a greater desire to participate in outdoor recreational and social activities, with a prevalence of >35%.

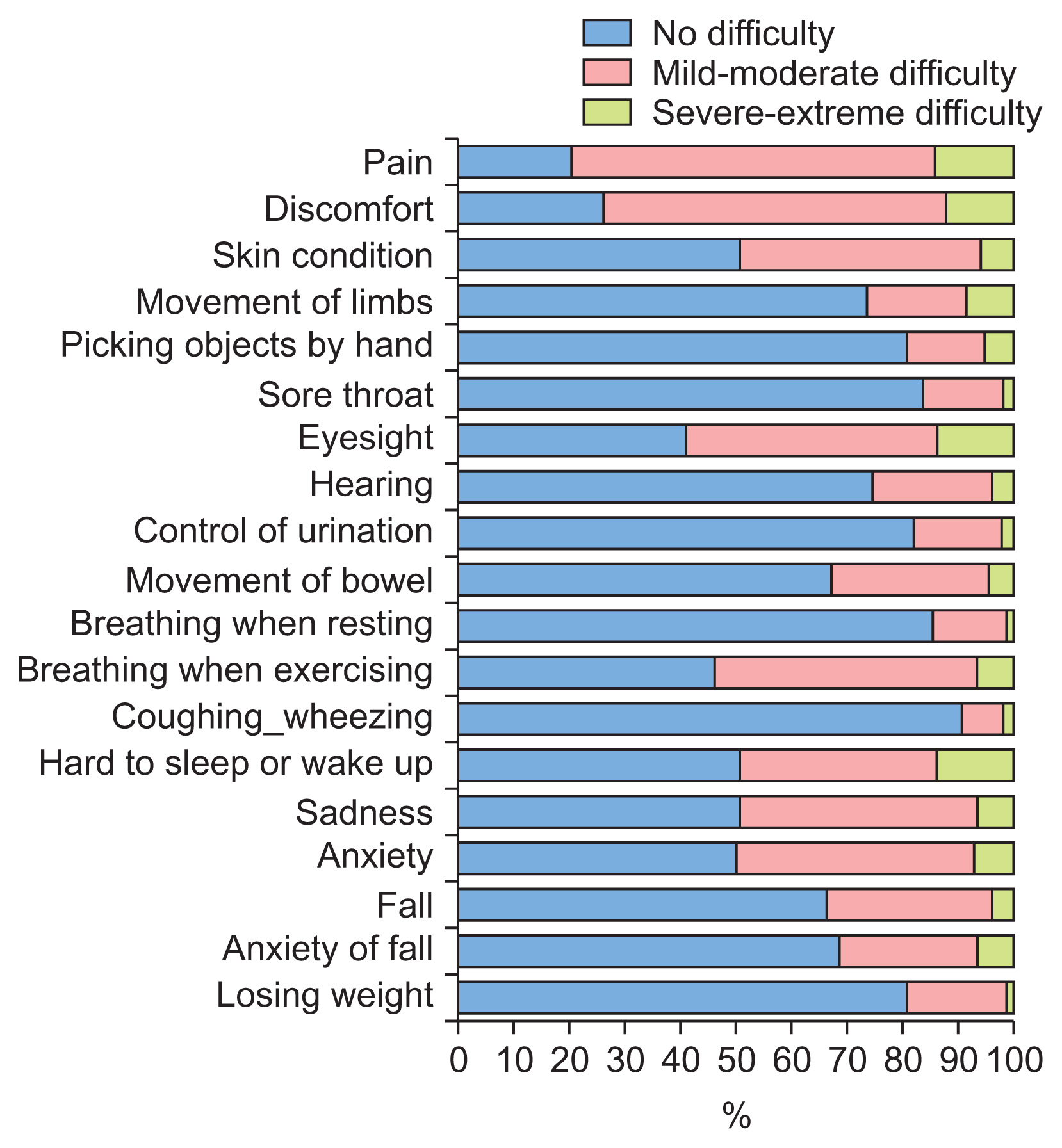

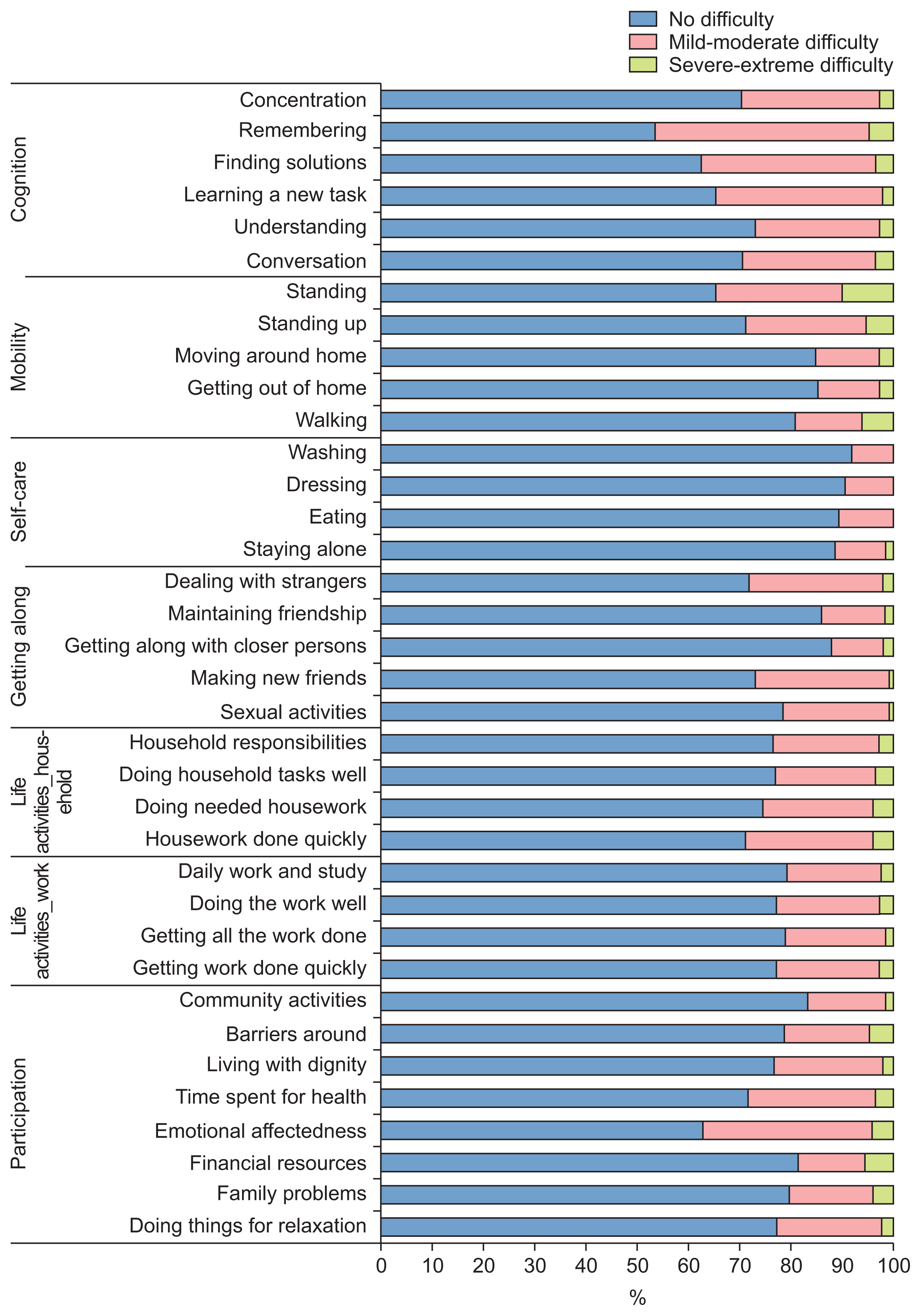

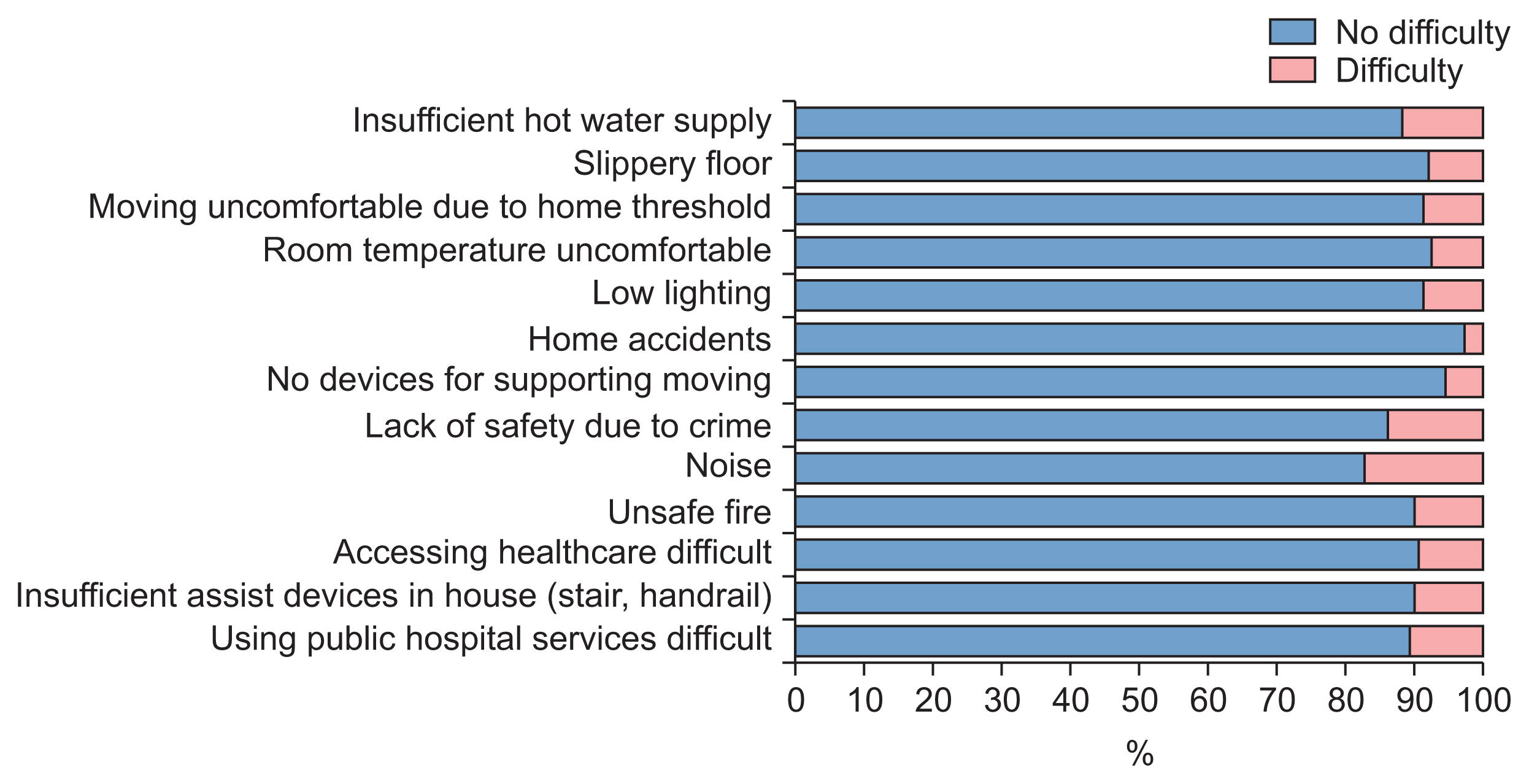

Regarding physical health assessment, participants’ impairment levels ranged from 10% to 80% (Figure 5). The highest levels of impairment were reported for pain and discomfort, accounting for 79.4% and 73.5% of participants, respectively. Difficulties in activities and in participation were reported by 10%–45% of participants (Figure 6). The total WHODAS 2.0 score for the 36 items of activity and participation was 12.16 (standard deviation 15.09), which means the participants experienced difficulties performing activities and participating in their daily life, but they did not yet have disabilities in performing these tasks. In the assessment of environmental problems (Figure 7), the most common problem that participants experienced in their homes was noise (17%), followed by a lack of safety due to crime and an insufficient hot water supply, which were reported by 14% and 12% of participants, respectively.

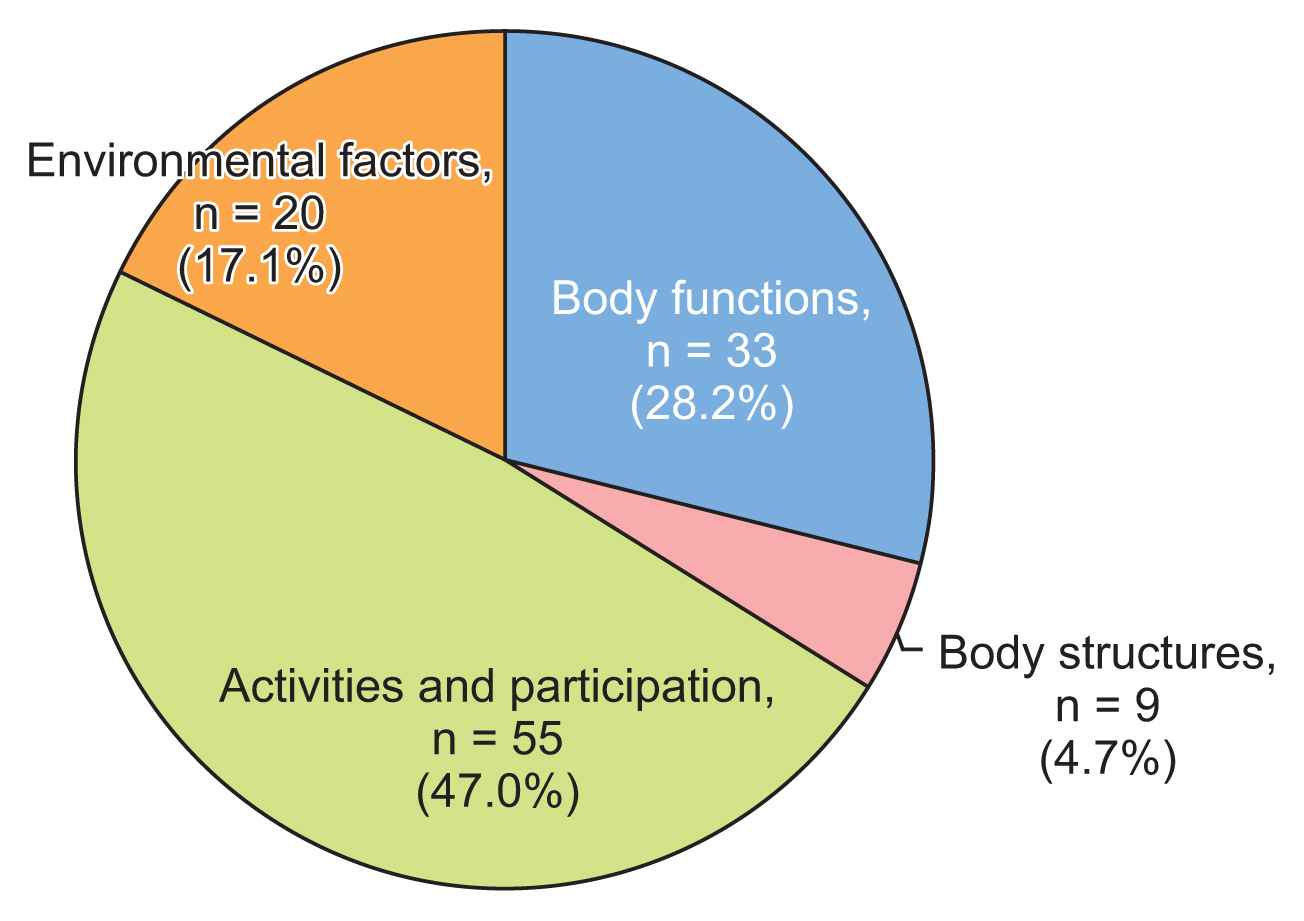

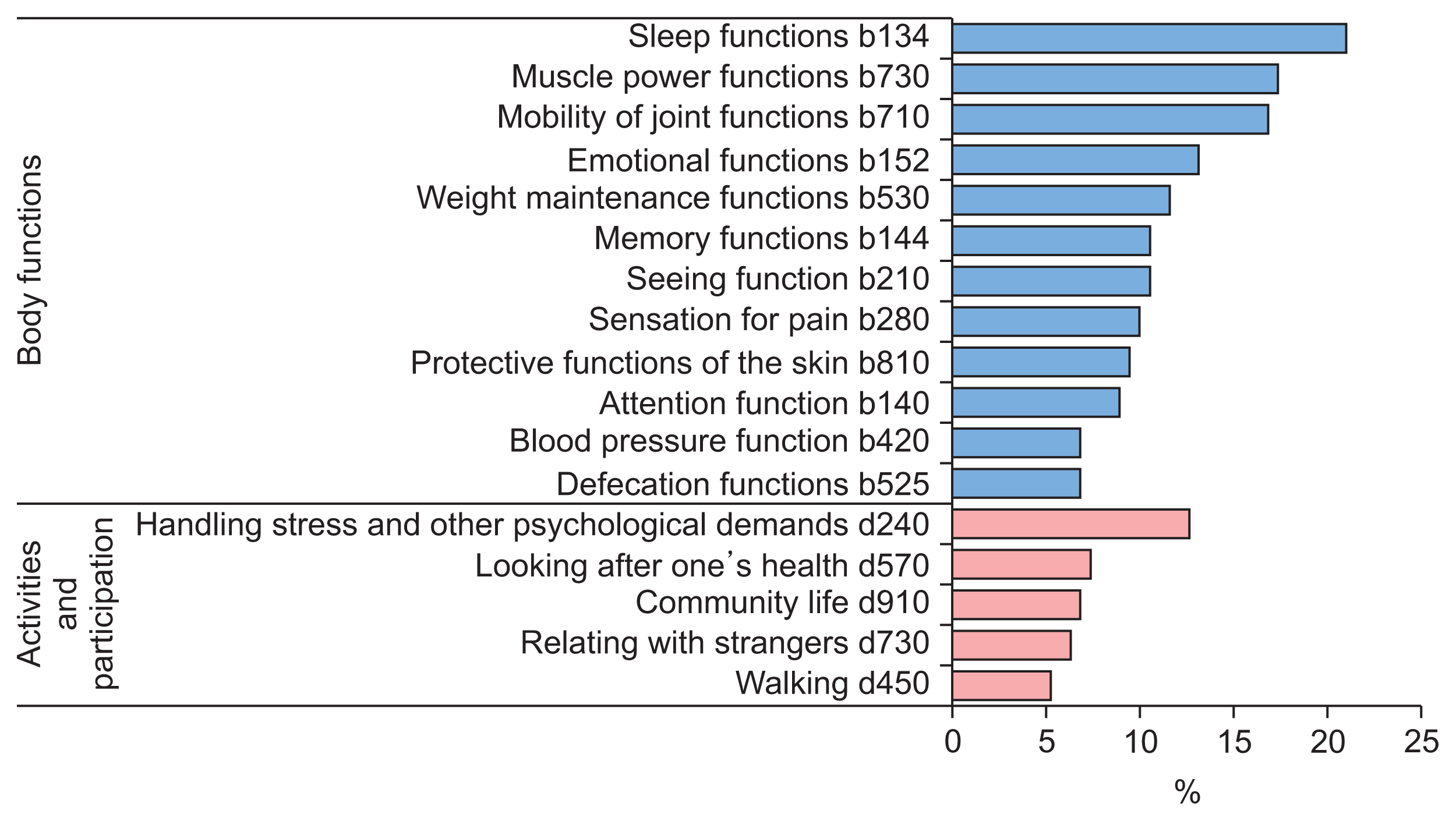

The health and social needs among community residents were matched to 117 ICF categories, which covered all ICF components, with the most common being activities and participation (47%), followed by body functions (28.2%) (Figure 8). Figure 9 presents the most frequently reported needs, which related to body functions and activities/participation. Within the “body functions” ICF component, the most frequently reported issues were with sleep functions (20.1%), muscle power functions (17.4%), and mobility of joint functions (16.8%). Within the activities and participation component, the most common need among participants (12.6%) was handling stress and other psychological demands (12.6%).

In the present study, younger individuals and women predominated among users of the community care platform. About 15.3% of the participants who used the online community care platform to evaluate their health and social needs were older than 65 years. These tendencies were also recognized in a previous study, in which digital health stations to monitor one’s health and access relevant health information were most frequently used by women (55.87%) and younger individuals (62.78% users less than 44 years), with only around 11% of users being over 65 years old [27]. An explanation for these results is that younger people tend to be more comfortable and active in seeking technologies that might facilitate their health [28]. Older adults face barriers and concerns about adopting new technology and they use health technologies at lower rates [29].

The findings of the current study present several advantages and areas for improvement in the CHSNA system. Assessment items were rated using a scale containing facial-expression icons to make the questions easier to answer. Using pictograms or graphic images could help persons with lower literacy improve their understanding of health-related education and medication information [30]. In this study, the actual use of the platform to assess needs was relatively acceptable over the 2-month period (about 47.7%). The participants were not required to use the platform; instead, they were encouraged to use the platform as they needed. This should be considered when attempting to improve the system and increase its completion rate. Several functions should be supplemented in an updated version to support more users, such as providing a chatbot to communicate with a supporter regarding participants’ questions or difficulties experienced when using the platform; alerts when the user skips any assessment item (intentionally or not), or not allowing users to move to the next step if any assessment item is left blank. Text message reminders should also be implemented to remind the user to complete their assessment.

In the present study, 117 ICF categories were exported from the platform; these factors were covered by the ICF components of body functions and structures, activities and participation, and environmental factors. Only the needs linked to the ICF categories of body functions and activities and participation were commonly reported, consistent with the ICF primary care setting focused on the functional status of individuals in primary care. However, only 17 ICF categories were frequently recorded (i.e., by more than 5% of participants) in the present study. This may be explained by the fact that the ICF contains more than 1400 categories that were mapped onto the present system, which may lead to a broad spread of ICF categories. A core set of ICF categories that are likely the most relevant to community residents should be generated. This core set may help the characterization and better understanding of the common health and social needs of community residents and may facilitate the provision of sufficient tailored interventions for these needs. The ICF categories selected in this study could provide input for the development of the core set of the most relevant future health and social needs for community residents.

This study had several strengths. Firstly, a broad view was taken when identifying the health and social needs of the general population by including a variety of age groups rather than focusing on a single group. It was necessary to classify the personal factors, which include individual characteristics such as race, gender, and education level [13]. Personal factors were included to provide a comprehensive understanding of the health and social needs of community residents from their individual perspectives. Potential limitations should also be mentioned; in particular, the included population was small and was obtained by convenience sampling, so the findings should be interpreted with caution.

In conclusion, community residents are faced with challenges in their daily lives, and many unmet needs were identified. Determining health and social needs requires a comprehensive assessment. The ICF may be suitable for determining the needs of community residents, and it could be integrated into information and communication-based applications that serve community care effectively. The analysis performed in this study provides insights into the present platform by identifying necessary improvements for optimizing the system to deliver best-fit care services for community residents.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Community Business Development Program through the Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy (No. P0013013).

Figure 1

Comprehensive Health and Social Needs Assessment system (CHSNA) on the Online Community Care Platform is mapped to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF). Screenshot 1 illustrates the first assessment step in the CHSNA-basic health assessment, which evaluates personal information and health status corresponding to the ICF personal factors component. Screenshot 3.1 shows a summary of physical health impairment mapped to body functions and structures in the ICF. Screenshots 3.2 and 3.3 present difficulties related to activities/participation and environmental problems, which are associated with the ICF components of activities/participation and environmental factors, respectively.

Figure 2

Result of the Comprehensive Health and Social Need Assessment system. ICF: International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health.

Figure 3

Number of users who completed each assessment step of the Comprehensive Health and Social Need Assessment system.

Figure 4

Percentage of community residents with needs for daily living activities. The screenshots on the left side are displayed as infographics to evaluate individuals’ needs for five domains of daily living activities (activities of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living, indoor recreational and leisure activities, outdoor recreational and leisure activities, social participation activities). The prevalence of having a need for a particular activity is presented as the corresponding item in the bar charts on the right side.

Figure 8

Proportion of ICF second-level domains in each category that were linked to the health and social needs of community residents in this study. ICF: International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health.

Figure 9

Top frequent health and social needs matching with ICF categories among community residents in the present study. ICF: International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health.

Table 1

Characteristics of the participants (n = 190)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age group (yr) | 42.7 ± 17.8 |

| 19–44 | 101 (53.2) |

| 45–64 | 60 (31.6) |

| ≥65 | 29 (15.3) |

|

|

|

| Sex | |

| Male | 31 (16.3) |

| Female | 159 (83.7) |

|

|

|

| Marital status | |

| Married or living together | 104 (54.7) |

| Single, divorced, or widowed | 86 (45.3) |

|

|

|

| Educationa | |

| Low | 22 (11.6) |

| Middle | 87 (45.8) |

| High | 81 (42.6) |

|

|

|

| Smoking | |

| Yes | 32 (16.8) |

| No | 158 (83.2) |

|

|

|

| Drinking alcohol | |

| Yes | 147 (77.4) |

| No | 43 (22.6) |

|

|

|

| Disability | |

| Yes | 12 (6.3) |

| No | 178 (93.7) |

|

|

|

| Chronic conditionb | |

| Yes | 64 (33.7) |

| No | 126 (66.3) |

|

|

|

| Common chronic conditionsc | |

| Hypertension | 33 (17.4) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 18 (9.5) |

| Arthritis | 11 (5.8) |

| Diabetes | 11 (5.8) |

| Other | 32 (16.8) |

References

1. World Health Organization. WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services: interim report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015.

2. Baxter S, Johnson M, Chambers D, Sutton A, Goyder E, Booth A. The effects of integrated care: a systematic review of UK and international evidence. BMC Health Serv Res 2018 18(1):350.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3161-3

3. Alderwick H, Ham C, Buck D. Population health systems: going beyond integrated care (The King’s Fund Report). Boston (MA): Policy Commons; 2015.

4. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Implementation of social services (community care) based on the community [Internet]. Sejong, Korea: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2018 [cited at 2022 Jun 30]. Available from: http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/al/sal0301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=04&MENU_ID=0403&CONT_SEQ=344177&page=1

5. World Health Organization. Strengthening people-centered health systems in the WHO European Region: framework for action on integrated health services delivery. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016.

6. Han KT, Park EC, Kim SJ. Unmet healthcare needs and community health center utilization among the low-income population based on a nationwide community health survey. Health Policy 2016 120(6):630-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.04.004

7. Kim YS, Lee J, Moon Y, et al. Unmet healthcare needs of elderly people in Korea. BMC Geriatr 2018 18(1):98.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0786-3

8. Jung B, Ha IH. Determining the reasons for unmet healthcare needs in South Korea: a secondary data analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2021 19(1):99.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-021-01737-5

9. Harrison F, Low LF, Barnett A, Gresham M, Brodaty H. What do clients expect of community care and what are their needs? The Community care for the Elderly: Needs and Service Use Study (CENSUS). Australas J Ageing 2014 33(3):206-13. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.12118

10. Ustun TB, Kostanjsek N, Chatterji S, Rehm J. Measuring health and disability: manual for WHO disability assessment schedule (WHODAS 20). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010.

11. Philip KE, Alizad V, Oates A, Donkin DB, Pitsillides C, Syddall SP, et al. Development of EASY-Care, for brief standardized assessment of the health and care needs of older people; with latest information about cross-national acceptability. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014 15(1):42-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2013.09.007

12. Reynolds T, Thornicroft G, Abas M, Woods B, Hoe J, Leese M, et al. Camberwell Assessment of Need for the Elderly (CANE): development, validity and reliability. Br J Psychiatry 2000 176:444-52. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.176.5.444

13. Alford VM, Ewen S, Webb GR, McGinley J, Brookes A, Remedios LJ. The use of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health to understand the health and functioning experiences of people with chronic conditions from the person perspective: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil 2015 37(8):655-66. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.935875

14. World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001. [cited at 2022 Jun 30]. Available from: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health

15. Jelsma J. Use of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: a literature survey. J Rehabil Med 2009 41(1):1-12. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-0300

16. Dernek B, Esmaeilzadeh S, Oral A. The utility of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health checklist for evaluating disability in a community-dwelling geriatric population sample. Int J Rehabil Res 2015 38(2):144-55. https://doi.org/10.1097/MRR.0000000000000101

17. Jayakumar P, Overbeek CL, Lamb S, Williams M, Funes CJ, Gwilym S, et al. What factors are associated with disability after upper extremity injuries? A systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2018 476(11):2190-215. https://doi.org/10.1097/CORR.0000000000000427

18. Cerniauskaite M, Quintas R, Boldt C, Raggi A, Cieza A, Bickenbach JE, et al. Systematic literature review on ICF from 2001 to 2009: its use, implementation and operationalisation. Disabil Rehabil 2011 33(4):281-309. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2010.529235

19. Howard D, Nieuwenhuijsen ER, Saleeby P. Health promotion and education: application of the ICF in the US and Canada using an ecological perspective. Disabil Rehabil 2008 30(12–13):942-54. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280701800483

20. Park M, Bui LK, Jeong M, Choi EJ, Lee N, Kwak M, et al. ICT-based person-centered community care platform (IPC3P) to enhance shared decision-making for integrated health and social care services. Int J Med Inform 2021 156:104590.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2021.104590

21. Park M, Choi EJ, Jeong M, Lee N, Kwak M, Lee M, et al. ICT-based comprehensive health and social-needs assessment system for supporting person-centered community care. Healthc Inform Res 2019 25(4):338-43. https://doi.org/10.4258/hir.2019.25.4.338

22. Ministry of Culture Sports and Tourism. National Leisure Activity Survey 2018 [Internet]. Sejong, Korea: Ministry of Culture Sports and Tourism; 2019 [cited at 2022 Jun 30]. Available from: https://www.mcst.go.kr/kor/s_notice/press/pressView.jsp?pSeq=17085

23. Ustun TB, Chatterji S, Villanueva M, Bendib L, Celik C, Sadana R, et al. WHO multi-country survey study on health and responsiveness 2000–2001. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001.

24. Korean Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Community Health Survey 2016 [Internet]. Cheongju, Korea: Disease Control and Prevention Agency; 2017 [cited at 2022 Jun 30]. Available from: https://chs.kdca.go.kr/chs/recsRoom/healthStatsMain.do

25. Lee M, Heo HH. Investigating similarities and differences in health needs according to disability type using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Disabil Rehabil 2021 43(26):3723-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1773941

26. Rast FM, Labruyere R. ICF mobility and self-care goals of children in inpatient rehabilitation. Dev Med Child Neurol 2020 62(4):483-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.14471

27. Flitcroft L, Chen WS, Meyer D. The demographic representativeness and health outcomes of digital health station users: longitudinal study. J Med Internet Res 2020 22(6):e14977.https://doi.org/10.2196/14977

28. Bol N, Helberger N, Weert JC. Differences in mobile health app use: a source of new digital inequalities? Inf Soc 2018 34(3):183-93. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2018.1438550

29. Fischer SH, David D, Crotty BH, Dierks M, Safran C. Acceptance and use of health information technology by community-dwelling elders. Int J Med Inform 2014 83(9):624-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2014.06.005

30. Mbanda N, Dada S, Bastable K, Ingalill GB, Ralf WS. A scoping review of the use of visual aids in health education materials for persons with low-literacy levels. Patient Educ Couns 2021 104(5):998-1017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2020.11.034