|

|

- Search

| Healthc Inform Res > Volume 27(1); 2021 > Article |

|

Abstract

Objectives

Stuttering is a speech disorder characterized by the repetition of sounds, syllables, or words; prolongation of sounds; and interruptions in speech. Telepractice allows speech services to be delivered to patients regardless of their location. This review investigated factors influencing the use of telepractice in stuttering treatment.

Methods

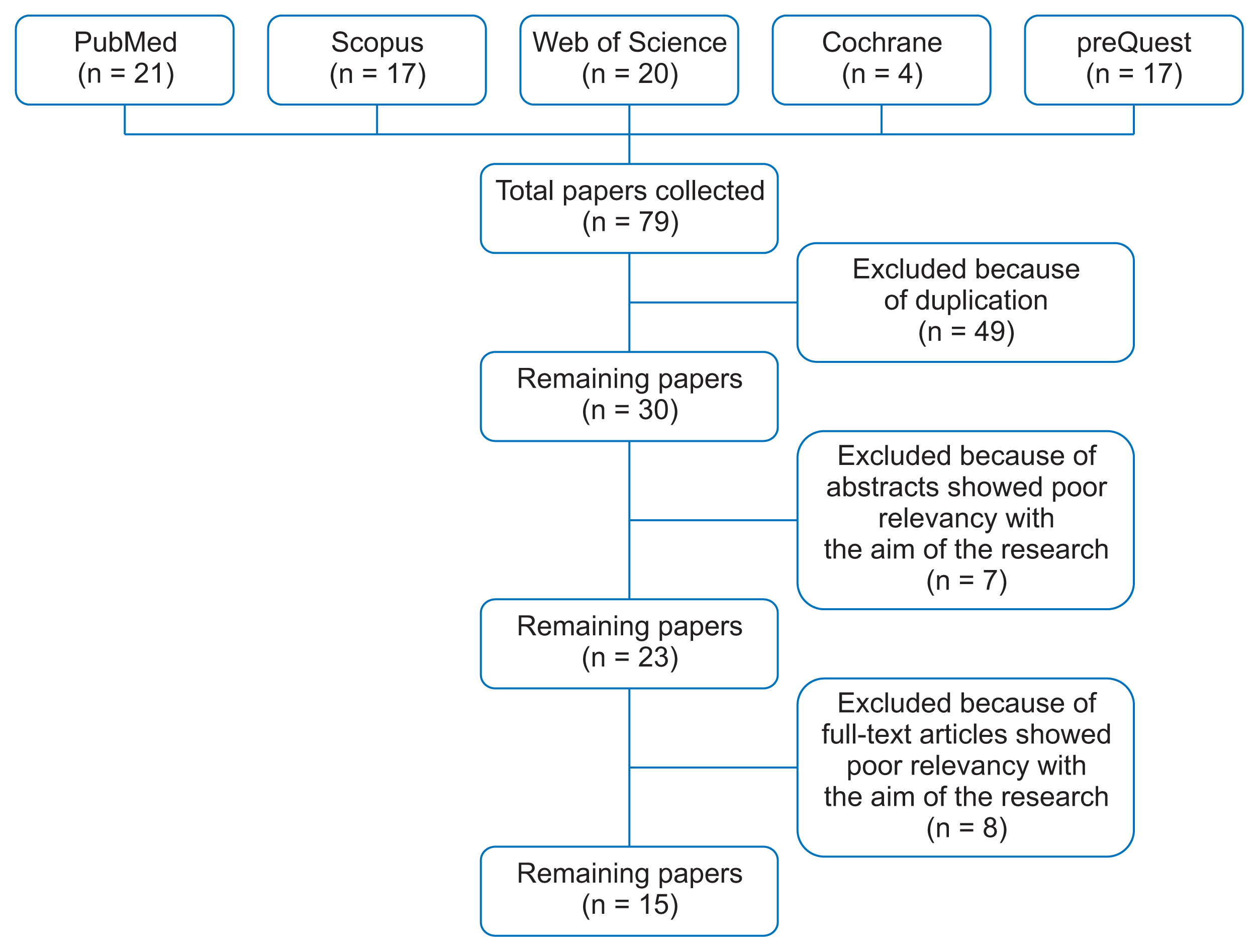

Articles related to the application of telepractice in stuttering were searched using the Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, Cochrane, and Pro-Quest databases without consideration of any time limit. Initially, 79 articles were found and after application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 15 articles were selected for the review study. Data were analyzed by using the content analysis method and synthesized narratively.

Results

Factors influencing the use of telepractice in stuttering treatment were categorized into individual, technical, clinical, and economic factors. Providing access to healthcare services, maintaining personal privacy, and allowing flexibility in arranging appointments were among individual factors. In terms of the technical factors, technical problems and Internet speed were addressed. Clinical factors were divided into positive and negative outcomes, and economic factors were mainly related to time and cost savings.

Conclusions

Although patients may benefit from using telepractice, the widespread adoption of this technology can be hindered by some technical and non-technical factors. Because telepractice can be employed as a complementary method to treat stuttering, more attention should be paid to the required infrastructure and factors that may negatively impact the use of this technology.

Stuttering, also known as stammering, is a speech disorder characterized by the repetition of sounds, syllables, or words; prolongation of sounds; and interruptions in speech known as blocks. Patients who stutter might resort to various strategies to overcome their problems, such as replacing problematic words or avoiding stressful situations [1]. In addition, communication failure and low self-confidence have significant impacts on the quality of life in patients who stutter [2]. Stuttering is a chronic disorder, so to achieve long-term treatment effects, patients are given the opportunity to continue therapy sessions if deemed necessary [3].

Although face-to-face healthcare delivery is considered a routine way of service delivery, sometimes accessing in-person speech therapy services can be difficult [4]. Hence, telepractice can be regarded as an alternative or supplemental model for care delivery and can provide healthcare services at the point of need [4,5]. Moreover, remote follow-up can cause the least inconvenience in patients’ daily routines [6].

The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) defines telepractice as the application of telecommunications technology in the delivery of speech language pathology services at a distance [7]. These services are delivered in synchronous, asynchronous, or hybrid forms. In the synchronous method, both patient and specialist have to be in touch simultaneously and exchange information at the same time. However, in an asynchronous communication, it is not necessary for the specialist and patient to communicate simultaneously, and in the hybrid form, both approaches can be used. Overall, telepractice is an appropriate service delivery model in speech language pathology for adults [8], and it can improve quality of healthcare, healthcare services accessibility, and subsequent equity in health. It can save costs and reduce patients’ waiting times, as well [5,9]. However, similar to other telemedicine services, there is the potential for technical difficulties and threats to patient privacy [10,11].

While a number of previous studies have been conducted to investigate the effectiveness of telepractice in stuttering treatment, it seems that evidence regarding this approach is scarce. For example, Lowe et al. [12] reviewed the application of asynchronous, synchronous, and hybrid telepractice in stuttering treatment and found that there is not enough evidence to confirm the efficacy of stuttering assessment via telepractice. Moreover, clinical and technical guidelines should be developed to support telepractice service delivery. In another study, McGill et al. [13] reported that synchronous telepractice can be a useful method for treating stuttering. However, asynchronous telepractice is more suitable for low-resource settings because it does not need to be supported by a complex information technology infrastructure [14]. It seems that previous studies have focused more on the service delivery and clinical and technical aspects of using telepractice rather than factors influencing the successful implementation or use of this technology. It is notable that the effectiveness of telepractice in stuttering treatment depends upon the level of service usage, which in turn might be affected by many different factors, such user satisfaction, patient’s age, and quality of communication [6,8,10]. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate factors influencing the use of telepractice in stuttering treatment.

This review study was completed in 2019. Initially, appropriate keywords were selected to find relevant articles. The keywords included telemedicine, mobile health, mHealth, m-Health, telehealth, eHealth, e-Health, telerehabilitation, tele-rehabilitation, remote rehabilitation, telepractice, virtual rehabilitation, telespeech therapy, speech therapy, fluency disorder, speech disorder, rehabilitation of speech, language disorders, stammer, and stuttering.

The keywords were searched in the Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, Cochrane, and ProQuest databases in combination by using Boolean operators (AND/OR), and all relevant papers were searched up to July 21, 2019. As the researchers focused on the factors influencing the use of telepractice in stuttering treatment, the original papers in which telepractice was used for patients with stuttering were selected to be included in the study. Conference papers, review articles, technical reports, books, e-books, and letters to the editor, non-English articles, those articles with no full-text available, and any paper related to the use of telepractice in other speech disorders were excluded from the study.

Initially, 79 articles were retrieved, and 49 duplicate articles were removed. The remaining 30 articles entered into the screening process. Because the aim of the research was to investigate factors influencing the use of telepractice in stuttering treatment, both authors collaborated to select the most relevant articles and assessed the eligibility of each article until consensus was reached. At that stage, those papers in which there was no result about the technical or non-technical factors influencing the use of telepractice showed poor relevancy to the aim of the research and were excluded. Finally, 15 articles were selected to be included. Figure 1 shows the process of paper selection.

Data were extracted using a data extraction form which consisted of several variables, namely, the name(s) of the author(s), year of publication, country, research objective, methods, participants, telepractice mode, and a summary of results.

Having reviewed the articles, the results showed that, in terms of the distribution of the published papers per country, Australia had the largest number of published papers (n = 11) and the remaining papers were from Canada (n = 2), Iran (n = 1), and Scotland (n = 1). In addition, most of the studies were published in 2014. A summary of the selected papers is presented in Table 1.

Most of the reviewed studies focused on stuttering assessment [6,9,10,15–24], and two studies were conducted to follow-up patients using telepractice [11,25]. Asynchronous services were applied in six studies [9,11,16,18,19,24], synchronous services were used in five studies [10,15,22,23,25], and hybrid services were adopted in four studies [17,20,21, 23]. Lewis et al. [17] provided the patients with telephone consultations, whereas in other studies communication was held via the Internet. About half of the studies used audio data [5,9,11,16–19,24], and in eight studies audio and visual data were collected for synchronous assessment, treatment, and follow-up of patients [5,10,15,20–23,25]. The most common application used in these studies was Skype [10,20,21, 23].

Most studies were interventional to measure the effect of telepractice and compare it with face-to-face visits [5,9,11,15,17–23]. Other studies evaluated the feasibility of implementing telepractice [24], patient satisfaction with the infrastructure used in telepractice [10], and the outcome of technology use for patient care [9,16,25].

The results showed that the factors influencing the use of telepractice could be divided into four groups of individual, technical, clinical, and economic factors (Table 2). This classification was based on the results derived from reviewing the selected papers. There might be other factors that were not considered in this study mainly due to the limitations in searching other databases, getting access to the full text of other relevant articles, and selecting the specific type of research papers to be included in this study.

In the study of Kully [25], the results showed that in synchronous communication, the technician’s presence in a telepractice session may have a negative impact on patients’ privacy and patients’ comfort in addressing speech-related problems. However, asynchronous and written communication, such as email, may provide a better relationship between the therapist and patient and encourage patients to share their emotions and attitudes more freely. In addition, telepractice, especially its asynchronous mode, is preferable for shy patients who cannot refer to the therapist in person for any reason [11].

Accessibility problems due to geographical distances can be also eliminated via telepractice [15,17,24]. In addition, the flexibility of this method allows patients to upload their speech samples into the system as permitted by their daily schedules [24]. Therefore, parents and children spend less time off from work and school and can follow their treatment programs after school and working hours [5,21,22,24].

System ease of use and the quality of voices and visual images are important for specialists to make accurate judgments about patients’ speech performance; however, making judgments about subtle visual features like speech breathing is difficult via telepractice [25].

In a study conducted by Sicotte et al. [15] clinical specialists evaluated the audio-visual quality and timeliness of received signals and found that they were satisfactory. However, in some studies, parents were dissatisfied with technical problems related to webcam communication, which was mostly caused by poor Internet connections [5,20,22]. In another study, the results indicated that low audio-visual quality prevented a good understanding of instructions and exercises presented by the speech therapist. Moreover, eye contact, which is an important factor in communication, was not well established [10].

Clinical factors can be divided into two groups of positive and negative clinical outcomes. Most of the studies showed that telepractice had positive clinical outcomes and there were significant reductions in stuttering frequency and severity compared to traditional face-to-face treatment sessions [9,15–17,20–23]. Moreover, a reduction in situation avoidance was also reported [19,21]. Ferdinands and Bridgman [23] measured stuttering severity in patients who received telepractice and those who attended clinics. The results showed that there was no significant statistical difference between these two groups. Lewis et al. [17] reported a 75% reduction in the syllables stuttered in the experimental group compared to the control group nine months after intervention, and there was a significant statistical difference between telepractice and face-to-face visits.

Individuals diagnosed with stuttering usually avoid situations that are stressful for speaking; however, situation avoidance decreases following treatment for stuttering [21]. In asynchronous communication, it seems that learning rehabilitation patterns is easier for patients, and there is sufficient time to practice speech techniques and error correction [11,18]. This can improve the level of self-care and quality of life among patients who stutter [19]. In addition, patients who are unable to communicate verbally because of extreme stuttering can communicate asynchronously in a written form to assist clinicians in decision-making and the development of care plans [11]. The results of other studies also indicated that patients feel more comfortable when they use telepractice in their own homes, and patients’ adherence to treatment protocols improves [5,10,11,21].

Despite the positive clinical outcomes of telepractice, some studies showed that there were several obstacles in creating effective relationships between the specialist and shy children whose speaking tone is low. This may reduce the quality of treatment [15]. In addition, it is very difficult to get the attention of children who are very comfortable at home [22]. In another study, Erickson et al. [19] found that the asynchronous method without the presence of the speech therapist is not appropriate for all patients, and the audio data are not sufficient to measure the syllables stuttered effectively [24]. Similarly, O’Brian et al. [22] reported that the use of synchronous methods, such as speech therapy through webcam is more effective than using low-technology methods, such as telephone and email. Moreover, communication via email may cause misunderstanding of the text either by the patient or by the therapist due to its written nature [11].

As noted in many studies, telepractice saves time and costs by eliminating unnecessary travel to clinics and reducing waiting times [10,19,21]. However, contradictory results were reported about the number and duration of telepractice sessions. The findings of the study conducted by Bridgman showed that the number of consultation sessions in telepractice was similar to the number of face-to-face visits [5]. The results of the studies in which telepractice was provided to preschool children demonstrated that the duration and number of therapy sessions increased in comparison to face-to-face visits [16,17,22]. However, Carey et al. [18,20] found that the group receiving telepractice required less time to complete their treatment plans in comparison to the other group who received face-to-face visits.

Telepractice is the application of telecommunication technology in speech language pathology and audiology professional services. This technology enables clinicians and patients to communicate at a distance [7]. The aim of this study was to investigate factors influencing the use of telepractice in stuttering treatment. The research findings showed that these factors can be divided into four groups of individual, technical, clinical, and economic factors.

Stuttering is a communication disorder; therefore, written communication as part of telepractice helps patients to communicate with their therapists more effectively [11]. Moreover, patients may feel more comfortable at home and have greater motivation to adhere to their treatment plans when they use telepractice [5,10,11,21]. These findings are supported by the results of other studies in which telepractice improved the accessibility of healthcare services and reduced the barriers associated with face-to-face visits. This, in turn, influenced patients’ attitudes positively, and as a result, patient cooperation during treatment was improved [26]. A study conducted by Eslami Jahromi et al. [27] showed that there was a significant difference in the mean scores of stuttering severity before and after telepractice and more than half of the patients were satisfied with this treatment method. Similarly, Cangi and Togram [4] showed that telepractice is as effective as in-person therapy for adults who stutter. However, there is a debate regarding economic factors. While, saving time and costs are considered among the positive economic factors encouraging the use of telemedicine services, such as telepractice, some researchers showed that in some cases the number and duration of treatment sessions may increase, which are costly for patients. One of the reasons for this issue can be differences in age groups undergoing treatment [28]. In addition, some studies used low-tech equipment to provide telespeech therapy [16,17], which can prolong the duration of treatment. Overall, the economic aspects of telepractice have rarely been studied, and the costs associated with new technologies have posed challenges to the sustainability of telepractice services [28]. The results of the current study suggested that evidence regarding the cost-effectiveness of telepractice is scarce and more research is required.

Although the implementation of telepractice seems to be beneficial, there are many challenges that may negatively influence its use in stuttering treatment. Maintaining patient privacy during treatment session is one of these challenges. In fact, no one should be present without the patient’s consent in a telepractice session, because the patient’s audio and visual information is completely confidential similar to other medical information [25]. Another challenge is related to the speed of the Internet, which makes it difficult to judge about audio specifications, and it can be considered as a technical barrier to implement telepractice effectively. In fact, factors such as low bandwidth and network congestion can lead to fluctuations in audio and visual quality [29]. Therefore, appropriate Internet bandwidth and adequate equipment are needed to reach the desired clinical outcomes when telepractice is applied [30].

Clinical factors, such as positive clinical outcomes, are encouraging factors to apply telepractice. Improvement in the severity and frequency of stuttering, reduction of situation avoidance, more time to practice speech techniques, improvement of self-care, assistance in the therapist’s decision-making, and increasing adherence to treatment protocols, are among the positive clinical outcomes [5]. Telepractice can promote self-care because it enables individuals to take more control over their own conditions and allows information about patients’ conditions to be monitored regularly. Therefore, clinicians can make better and more timely decisions [15]. However, factors such as misunderstanding of written information, insufficiency of audio data in evaluating stuttering, and a lack of physical examinations, as well as the inappropriateness of telepractice for children due to the difficulty in attracting their attention may cause negative clinical outcomes when telepractice is used [15]. In fact, telepractice is more suitable for children older than 6 years old, and age is an important factor that must be taken into account. Because telepractice services are based on audio, visual, and verbal interactions [10], real-time communication of the therapist and patient through web-conferencing can be more efficient compared to low-tech and written communication methods, such as email. On the other hand, to solve the problems caused by the impossibility of physical examination through telepractice, it is recommended to have face-to-face visits in the initial sessions to enable evaluation and diagnosis of the patient’s condition.

Overall, it seems that telepractice can be used as a complementary method to treat stuttering, and it cannot be considered a replacement for face-to-face visits. To improve the use of this technology, like other similar telemedicine technologies, it is important to pay more attention to the required infrastructure and control or minimize the effect of factors that may negatively influence its use.

Table 1

Summary of selected papers

| No. | Author, year | Location | Objective | Research method | Participants | Telepractice modes and equipment | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kully [25], 2000 | Canada | To report the videoconferencing application in providing follow-up support to geographically faraway adults who have undergone intensive treatment on the site | Case report | A 38-year-old man | Synchronous videoconferencing system |

There was difficulty in judgments about subtle visual features like speech breathing. There were concerns over the potential influence of the technicians’ presence on patient confidentiality and comfort. |

| 2 | Sicotte et al. [15], 2003 | Canada | To evaluate the feasibility and outcome of delivering remote speech–language services to children and adolescents who stutter | Pre-post study | 6 patients (4 children, aged 3–12 years, and 2 adolescents, aged 17–19 years) and 1 SLP | Synchronous/Polycom Viewstation MP, television monitor, omnidirectional microphones |

Technical and clinical quality was judged positively by the therapist and patients. There was difficulty in interacting adequately with agitated and shy children. The clinical outcome was positive and their fluency improved. The geographical accessibility problems were solved. |

| 3 | Wilson et al. [16], 2004 | Australia | To report the outcomes of a low-tech telepractice adaptation of the Lidcombe Program of early stuttering intervention | Case series | 5 children aged between 5 months to 3 years and 7 months to 5 years | Asynchronous/e-mail, telephone | Telepractice helped reduce stuttering frequency. The number of consultation sessions and time per consultation increased. |

| 4 | O’Brian et al. [9], 2008 | Australia | To investigate the viability of telepractice delivery of the Camperdown Program with adults who stutter | Case series (phase I) | 8 men and 2 women aged between 20 and 40 years | Asynchronous/telephone and e-mail | Telepractice helped reduce stuttering frequency and improved speech naturalness. |

| 5 | Lewis et al. [17], 2008 | Australia | To evaluate the efficacy of telepractice delivery of the Lidcombe program of early stuttering intervention | RCT (phase II) | 22 preschool-age children (aged 3–6 years) and their parents | Hybrid/telephone, audiotape record |

Telepractice helped reduce stuttering frequency. Access to speech therapy services was improved. In terms of economic factors, telepractice is not cost-effective for early stuttering treatment. |

| 6 | Carey et al. [18], 2010 | Australia | To investigate whether telepractice delivery of the Camperdown Program provides a non-inferior alternative to face-to face treatment for adults who stutter | Non-inferiority RCT | 36 adults aged 18 years and above | Asynchronous/tele-phone, voicemail | Telepractice takes fewer hours than face-to-face visits. The effectiveness of telepractice in reducing stuttering frequency and improving speech naturalness was the same as that of face-to-face visits. All participants were satisfied with the telepractice services mainly because of their ease of use. |

| 7 | Allen [11], 2011 | Scotland | To explore the viability of e-mail in appointment scheduling for patients who stutter | Pre-post study | 5 clients aged 19–52 years | Asynchronous/e-mail | Telepractice improved access to speech therapy services. Telepractice improved appointment scheduling, self-disclosure, and patient commitment to practice. Patients had enough time to practice speech techniques. There were problems with confidentiality, security and misunderstanding. |

| 8 | Carey et al. [20], 2012 | Australia | To explore the viability of webcam Internet delivery of the Camperdown Program for adolescents who stutter | Clinical trial (phase I) | 2 boys and 1 girl aged 13–16 years | Hybrid/Internet tele-conferencing with webcam and Skype software, e-mail | Telepractice reduced severity and frequency of stuttering and improved speech naturalness. Telepractice helped to save time. There were some technical issues. |

| 9 | Carey et al. [21], 2014 | Australia | To examine stuttering adolescents’ responsiveness to the webcam-delivered Camperdown Program | Clinical trial (phase II) | 14 boys aged 12–17 years | Hybrid/Internet teleconferencing with webcam and Skype software, e-mail | Telepractice reduced severity and frequency of stuttering as well as situation avoidance. Telepractice reduced unnecessary travel and disruption of daily activities. Telepractice increased patient commitment to treatment protocols. |

| 10 | Vogel et al. [24], 2014 | Australia | To investigate the feasibility of adopting automated IVR technology for remotely capturing standardized speech samples from stuttering children | Feasibility study | 10 children with an average age of 6 years and 5 months | Asynchronous/automated IVR system, voice over Internet protocol (VoIP), and a digital recorder | Telepractice improved simultaneous automated data collection across wide geographic areas. Families could manage their schedules and lifestyles. Audio files could not calculate the percentage of syllables stuttered efficiently. |

| 11 | O’Brian et al. [22], 2014 | Australia | To explore the potential efficacy, practicality, and viability of an Internet webcam Lidcombe Program service delivery model | Clinical trial (phase I) | 3 children (2 boys and 1 girl) aged 3 years and 6 months, 4 years and 3 months, and 4 years and 9 months, respectively, and their parents | Synchronous/computer with access to the Internet and a webcam | Telepractice reduced severity and frequency of stuttering. Telepractice helped to save time and costs. There were some technical problems. Children felt relaxed at home, which sometimes made it difficult to attract their attention. |

| 12 | Bridgman et al. [6], 2016 | Australia | To compare outcomes of clinic and webcam delivery of the Lidcombe Program treatment for early stuttering | Non-inferiority RCT | 49 children aged 3 years to 5 years and 11 months | Synchronous/computer with access to the Internet and a webcam | Telepractice helped to save costs. Telepractice had minimal effect on participants’ work-life balance. There were some Internet connection problems. Children’s frustration was another obstacle. |

| 13 | Erickson et al. [19], 2016 | Australia | To assess the viability of a clinician-free Internet presentation of speech restructuring treatment for chronic stuttering | Clinical trial (phase I) | A 20-year-old man and a 30-year-old woman | Asynchronous/computer with access to the Internet, interactive website | Telepractice reduced severity and frequency of stuttering as well as situation avoidance. Telepractice improved access to treatment. Telepractice helped to save costs and time. |

| 14 | Ferdinands and Bridgman [23], 2019 | Australia | To determine whether stuttering severity was correlated with parent satisfaction with child fluency during treatment and to demonstrate a non-inferiority finding for parent satisfaction between telepractice and clinic delivery of the Lidcombe Program | Parallel and non-inferiority RCT | 37 preschool boys and 12 preschool girls and their parents | Hybrid/computer with access to the Internet, a webcam and a live video calling program (Skype) | Telepractice reduced severity and frequency of stuttering. Parents were satisfied with telepractice services. |

| 15 | Eslami Jahromi and Ahmadian [10], 2018 | Iran | To assess the satisfaction of patients suffering from stutter with a concentration on the therapeutic method and the infrastructure used to receive tele-speech therapy services | Descriptive-analytical study | 30 patients aged between 14 and 39 years | Synchronous/computer with access to the Internet, Skype | Telepractice helped to save costs and time. There were some Internet connection problems. There were eye contact problems as well as poor image quality. |

Table 2

Summary of factors influencing the use of telepractice in stuttering

References

1. Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists. RC-SLT clinical guidelines. Oxon, UK: Speechmark Publishing; 2005.

2. Yadegari F, Shirazi TS, Howell P, Nilipour R, Shafiei M, Shafiei B, et al. Persian overall assessment of the speaker’s experience of stuttering for adults: the impact of stuttering on the Persian-speaking adults who stutter. Iran Rehabil J 2018;16:131-8.

3. Packman A, Onslow M. Investigating optimal intervention intensity with the Lidcombe Program of early stuttering intervention. Int J Speech Lang Pathol 2012;14:467-70.

4. Cangi ME, Togram B. Stuttering therapy through telepractice in Turkey: a mixed method study. J Fluency Disord 2020;66:105793.

5. Beijer LJ, Rietveld AC. Asynchronous telemedicine applications in the rehabilitation of acquired speech-language disorders in neurological patients. Smart Homecare Technol Telehealth 2015;3:39-48.

6. Bridgman K, Onslow M, O’Brian S, Jones M, Block S. Lidcombe Program webcam treatment for early stuttering: a randomized controlled trial. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2016;59:932-9.

7. Cason J, Cohn ER. Telepractice: an overview and best practices. Perspect Augment Altern Commun 2014;23(1):4-17.

8. Weidner K, Lowman J. Telepractice for adult speech-language pathology services: a systematic review. Perspect ASHA Spec Interest Groups 2020;5:326-38.

9. O’Brian S, Packman A, Onslow M. Telehealth delivery of the Camperdown Program for adults who stutter: a phase I trial. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2008;51:184-95.

10. Eslami Jahromi M, Ahmadian L. Evaluating satisfaction of patients with stutter regarding the tele-speech therapy method and infrastructure. Int J Med Inform 2018;115:128-33.

11. Allen CR. The use of email as a component of adult stammering therapy: a preliminary report. J Telemed Telecare 2011;17:163-7.

12. Lowe R, O’Brian S, Onslow M. Review of telehealth stuttering management. Folia Phoniatr Logop 2013;65:223-38.

13. McGill M, Noureal N, Siegel J. Telepractice treatment of stuttering: a systematic review. Telemed J E Health 2019;25:359-68.

14. Wootton R. Telemedicine in low-resource settings. Lausanne, Switzerland: Frontiers Media SA; 2015.

15. Sicotte C, Lehoux P, Fortier-Blanc J, Leblanc Y. Feasibility and outcome evaluation of a telemedicine application in speech-language pathology. J Telemed Telecare 2003;9:253-8.

16. Wilson L, Onslow M, Lincoln M. Telehealth adaptation of the Lidcombe Program of early stuttering intervention: five case studies. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 2004;13:81-93.

17. Lewis C, Packman A, Onslow M, Simpson JM, Jones M. A phase II trial of telehealth delivery of the Lidcombe Program of early stuttering intervention. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 2008;17:139-49.

18. Carey B, O’Brian S, Onslow M, Block S, Jones M, Packman A. Randomized controlled non-inferiority trial of a telehealth treatment for chronic stuttering: the Camperdown Program. Int J Lang Commun Disord 2010;45:108-20.

19. Erickson S, Block S, Menzies R, O’Brian S, Packman A, Onslow M. Standalone Internet speech restructuring treatment for adults who stutter: a phase I study. Int J Speech Lang Pathol 2016;18:329-40.

20. Carey B, O’Brian S, Onslow M, Packman A, Menzies R. Webcam delivery of the Camperdown Program for adolescents who stutter: a phase I trial. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch 2012;43:370-80.

21. Carey B, O’Brian S, Lowe R, Onslow M. Webcam delivery of the Camperdown Program for adolescents who stutter: a phase II trial. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch 2014;45:314-24.

22. O’Brian S, Smith K, Onslow M. Webcam delivery of the Lidcombe program for early stuttering: a phase I clinical trial. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2014;57:825-30.

23. Ferdinands B, Bridgman K. An investigation into the relationship between parent satisfaction and child fluency in the Lidcombe Program: clinic versus telehealth delivery. Int J Speech Lang Pathol 2019;21:347-54.

24. Vogel AP, Block S, Kefalianos E, Onslow M, Eadie P, Barth B, et al. Feasibility of automated speech sample collection with stuttering children using interactive voice response (IVR) technology. Int J Speech Lang Pathol 2015;17:115-20.

25. Kully D. Telehealth in speech pathology: applications to the treatment of stuttering. J Telemed Telecare 2000;6(Suppl 2):S39-41.

26. Marcin JP, Shaikh U, Steinhorn RH. Addressing health disparities in rural communities using telehealth. Pediatr Res 2016;79:169-76.

27. Eslami Jahromi M, Ahmadian L, Bahaadinbeigy K. The effect of tele-speech therapy on treatment of stuttering. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 2020;1-6.

28. Jafni TI, Bahari M, Ismail W, Radman A. Understanding the implementation of telerehabilitation at pre-implementation stage: a systematic literature review. Procedia Comput Sci 2017;124:452-60.

- TOOLS