|

|

- Search

| Healthc Inform Res > Volume 23(4); 2017 > Article |

Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to identify problems and issues that arise with the implementation of online health information exchange (HIE) systems in a medical environment and to identify solutions to facilitate the successful operation of future HIE systems in primary care clinics and hospitals.

Methods

In this study, the issues that arose during the establishment and operation of an HIE system in a hospital were identified so that they could be addressed to enable the successful establishment and operation of a standard-based HIE system. After the issues were identified, they were reviewed and categorized by a group of experts that included medical information system experts, doctors, medical information standard experts, and HIE researchers. Then, solutions for the identified problems were derived based on the system development, operation, and improvement carried out during this work.

Results

Twenty-one issues were identified during the implementation and operation of an online HIE system. These issues were then divided into four categories: system architecture and standards, documents and data items, consent of HIE, and usability. We offer technical and policy recommendations for various stakeholders based on the experiences of operating and improving the online HIE system in the medical field.

Conclusions

The issues and solutions identified in this study regarding the implementation and operate of an online HIE system can provide valuable insight for planners to enable them to successfully design and operate such systems at a national level in the future. In addition, policy support from governments is needed.

Nations around the world provide various medical information services. Among them, online health information exchange (HIE) services have been expanded internationally among hospitals and communities. Previous studies related to HIE have shown that adoption of HIE services leads to higher patient satisfaction due to stronger therapeutic intervention and improvements in patient outcomes [1234]. Furthermore, if patient clinical information is shared in a timely manner, the accuracy of diagnosis is improved, test duplication is reduced, and patient re-admission and medication errors can be prevented [56]. The purpose of HIE is to improve the quality of patient care through timely sharing of health information. Recently, health information services have been expanding into HIE environments between communities or countries beyond the exchange of health information in hospitals using advanced information processing technology and high-speed network infrastructure [7].

In the United States, medical information exchange systems have been implemented through the focus on medical information technology in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act enacted in 2009. This act establishes the roles and functions of the Office of the National Coordinator (ONC) for Health Information Technology and encourages the development of a medical information technology infrastructure that can be shared throughout the United States. The United States has carried out a variety of projects to develop online HIE systems at the national level, and every state in the United States decides on and improves policies at the state level while executing state-level projects. For online HIE methods, direct and query-based exchanges can be used, and most states employ both types of exchanges simultaneously [8]. France established the Agence des Systémes d'Information Partagés de Santé (L'ASIP Santè) to define a framework for the improvement of medical information sharing. The implementation of HIE profiles in France required additional setup to meet the requirements and the medical environment. They arranged profile vocabularies using the Classification Commune des Actes Médicaux (CCAM) and ICD-10, they used the HL7 Clinical Document Architecture (CDA) for clinical document standards, and they used Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC) and SNOMED for examination term standards [910]. The basic act for personal information protection in France is the Act on Data Processing, Files, and Individual Liberties, enacted in 1978. The enforcement ordinance of the act specifies detailed regulations for medical research requests for personal data [11]. In 2005, the National E-Health Transition Authority (NEHTA) was founded through funding from the Council of Australian Governments, which is the authority that is responsible for promoting access to e-Health sectors at the national level. For document exchange in the national central system, the Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise (IHE) Cross-Enterprise Document Sharing (XDS) standards were defined as the basic system, and the HL7 CDA was applied to standard HIE forms. Personal information protection in Australia is accomplished through a legal system that regulates the public and private sectors via a single legislative act [1213].

Korea has also made progress in the digitization of hospital tasks, and its online HIE system has been expanding between cooperating healthcare organizations. This study aimed to identify issues and considerations that arise in relation to the implementation and operation of online HIE systems. Thus, this study may provide insights to assist in the implementation of other online HIE systems through the identification of problems and possible solutions.

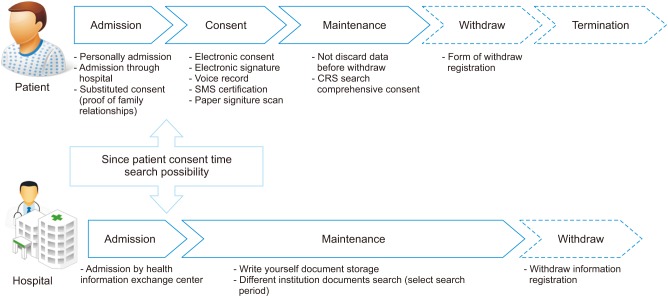

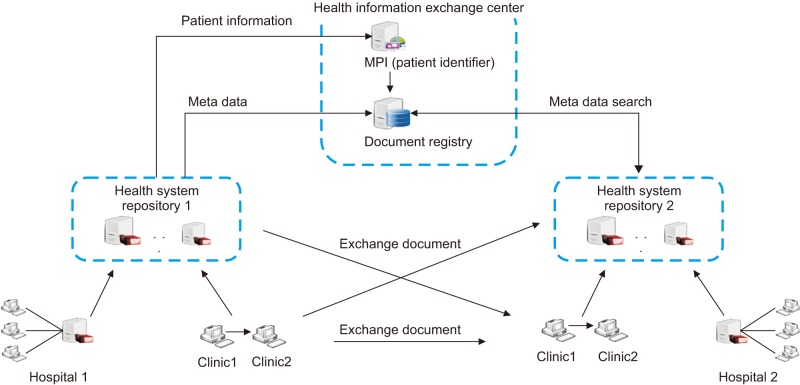

In this paper, we define a central registry and multiple repositories as a standardized architecture. An online HIE center manages the metadata and patients, and healthcare organizations are participants (Figure 1).

In the HIE system, the HL7 Consolidated CDA (C-CDA) was adopted, and referral notes, medical examination documents, and care record summaries (CRSs) were defined as the standard documents. To improve the information fidelity, we defined the values that are required and should be included if available [14]. The consent for online HIE was individual consent per event because of the medical act. Consent for the CRS was done collectively because patient care events occur frequently (Figure 2).

The standard-based online HIE system was used between one hospital and 44 primary care clinics. A total of 2,583 patients participated in online HIE for about 12 months from July 4, 2016 to June 30, 2017, during which 2,546 referrals and 161 transfers occurred. We attempted to understand the potential problems and barriers affecting the establishment and operation of HIE systems. We monitored and identified issues during the processes to establish a system for seamless HIE.

Prior to implementation of the system, we conducted scenario tests that included referrals, replies, transfers, and CRS creation from June 20 to July 1, 2016 to identify potential issues. Moreover, for stable operation of the HIE system, the issues identified during the operation after its opening were noted. To solve the identified issues, three medical information system experts, one medical information standard expert, four medical staff members, and two researchers of HIE systems compiled a list of such issues. These were then categorized into the four types, including usability, HIE contents (documents and data elements), system architecture and standards, and participants' informed consent, and regular meeting were held to find solutions for each issue. If any issues that arose during the operation of the system needed to be resolved quickly, they were addressed immediately through real-time online discussions. In addition, if a hospital policy needed to be modified to resolve the identified issues, an HIE task force team (TFT) of 11 medical staff members, three researchers, and three medical information system experts gathered for a TFT conference and determined the policies related to HIE within the hospital. The definition of standard terms and the issues requiring policy consensus were classified separately so that stakeholders, a manager of the Department of Health and Welfare, and a manager of the Social Security Information Center defined the terms and shared the need for policy amendments. When issues needed to be solved by alterations in the system, they were immediately implemented; when any terms needed to be defined, clear definitions were proposed. In the case of issues requiring further policy agreement, efforts to come to a policy consensus on the relevant issues were made, and the results were derived.

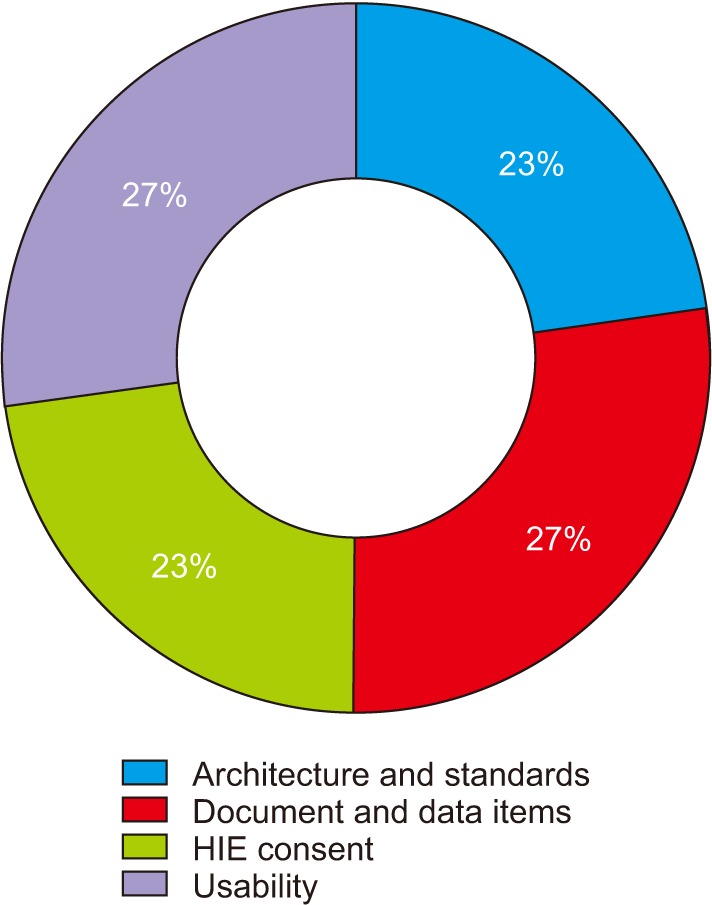

The identified issues were divided into categories according to which aspect of HIE implementation they concerned, namely, usability, documents and data, architecture and standards, and consent (Figure 3).

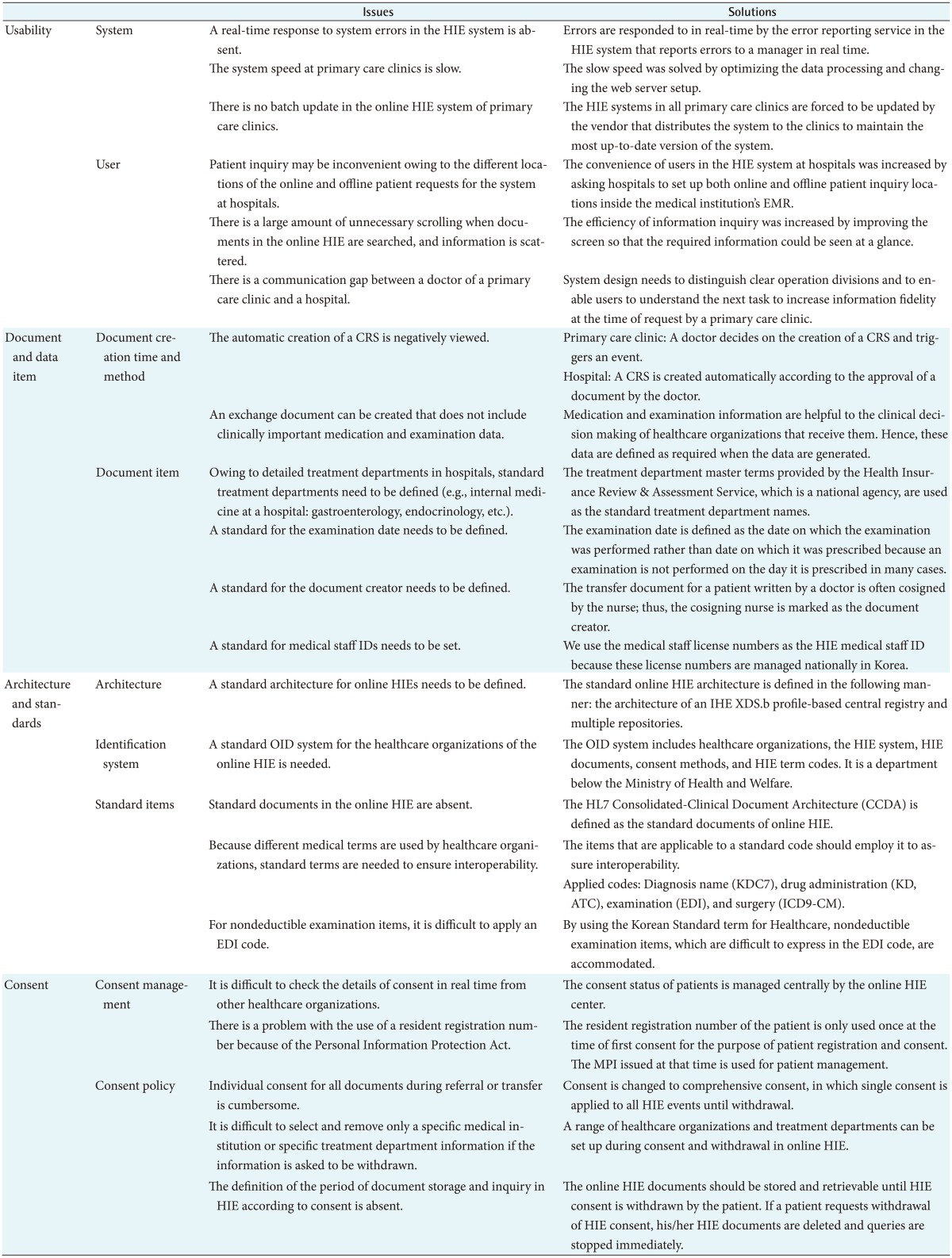

In total, 22 issues were identified and were divided into four categories (Table 1). Proposals and definitions were proposed as solutions to address the issues.

A previous study on medical system usability showed that by considering the usability requirements in system design, system can be used efficiently and effectively; therefore, we derived issues arising from the implementation of the HIE system from a user experience viewpoint [15]. The issues related to usability were identified from system errors, inconveniences, and user experiences of online HIE. Each of the usability issues and solutions is presented in Table 1. The most common issues were an absence of real-time error responses and a lack of a simple means of image file exchange, which were resolved by introducing additional services. The system usability issues in the primary care clinic were slow system speeds and the absence of a batch update function. These issues were resolved by improving the update method and web server setup. Improvements in the user experience (UX) and user interface (UI) of creation and inquiry screens are needed in the future to improve system usability.

Online HIE documents require clear definitions when being entered in the system; they are an important part that determines the quality of the data in an HIE. The issues found while defining documents and their solutions were determined prior to system operation (‘document and data items’ in Table 1). One issue related to document creation was raised because there were no detailed definitions for the circumstances of document creation. Hence, the process for creating a document was clearly defined to resolve this issue, and document items were redefined to be acceptable by all healthcare organizations.

We present the decisions and suggestions while defining the

architecture and implementing the system (‘architecture and

standards’ in Table 1). To resolve the need for a standard architecture

and identification system, we defined the standard

architecture and the OIDs of participating HIE institutions.

Among the standard code, the Korean EDI code was defined

by the examination code, but nondeductible examinations

were difficult to map to the medical fee codes. Hence, other

standards for healthcare terms were also used to address this

mapping problem.

In recent years, Korea has provided a legal basis for sharing health information appropriately among healthcare organizations. In the past, treatment records could be sent to other medical providers with the consent of the patient or guardian (Paragraph 3 of Article 21 in the Medical Act), and a copy of the treatment record could be forwarded when new patients were sent to other healthcare organizations (Paragraph 5 of Article 21 in the Medical Act) [16]. The consent method was modified to enable comprehensive consent according to the standard notification of HIE in Korea. Each of the consent issues and their solutions are listed in Table 1. To solve problems related to consent, a new consent method was added to the HIE system, and consent history management was changed to enable real-time queries about consent status. The consent policy issue relates to individual consent, which is the current consent method. To resolve this issue, a comprehensive consent method was proposed and defined to enable selective withdrawal of departments and healthcare organizations.

The HIE service has been expanding through cooperative healthcare organizations to increase the quality of medical services. In particular, an online HIE system was implemented by complying with information exchange standards to share health information between heterogeneous systems. This study summarized the issues that occurred during the implementation and operation of a standard-based online HIE system in Korea, and an effort was made to define concerns and resolve issues and thus operate the system reliably.

The issues derived from this study can be compared with those derived from HIE operations and experiences in France and North America. A major issue with the operation of the HIE program in France was the low participation of patients in the HIE due to opt-in consent policy. In addition, uncertainties in policy support and the difficulty of maintaining the technology were addressed in ways similar to the solutions adopted in our study [17]. Also, there have been issues regarding the lack of interoperability, high entry costs, and the lack of standards due to difficulties in adopting HIE across the United States, which are similar to the issues related to our architecture and standards documents [1819]. In this study, the issue of convenience for users of the HIE system was derived, and policy insights that need to be considered in the operation of HIE systems were derived.

This study was somewhat limited because the issues and results were identified through operations and diffusion in only one institution; thus the results reflect the characteristics of the specific context in which the study was conducted. Therefore, the results of this study might be difficult to generalize because they reflect the characteristics of the population in the area and the characteristics of medical personnel in the institution where it was carried out. However, we believe that organizations and administrators establishing HIE systems in the future can to implement successful and sustainable HIE systems and avoid unexpected barriers through consideration of our experience and by adopting the problem-solving techniques applied in this study. Furthermore, active and strategic participation of governments in the development of HIE services is required to solve management issues, such as design proposals, and consensus methods must be improved to enhance information exchange systems. Through this study, we hope to reduce the communication gaps among medical institutions, to contribute to the successful implementation of HIE systems, and to promote the nationwide diffusion of HIE.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (No. HI14C2756).

References

1. Unertl KM, Johnson KB, Gadd CS, Lorenzi NM. Bridging organizational divides in health care: An ecological view of health information exchange. JMIR Med Inform 2013;1(2):e3. PMID: 25600166.

2. Shade SB, Chakravarty D, Koester KA, Steward WT, Myers JJ. Health information exchange interventions can enhance quality and continuity of HIV care. Int J Med Inform 2012;81(10):e1-e9. PMID: 22854158.

3. Vest JR, Miller TR. The association between health information exchange and measures of patient satisfaction. Appl Clin Inform 2011;2(4):447-459. PMID: 23616887.

4. McGee MK. Health information enhances decision making [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): Information-Week; 2010. cited at 2017 Jun 16. Available from: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/clinicalinformation-systems/health-nformation-exchangeenhances-decision-making/d/d-id/1090004?page_number=1

5. Frisse ME, Johnson KB, Nian H, Davison CL, Gadd CS, Unertl KM, et al. The financial impact of health information exchange on emergency department care. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2012;19(3):328-333. PMID: 22058169.

6. Kaelber DC, Bates DW. Health information exchange and patient safety. J Biomed Inform 2007;40(6 Suppl):S40-S45. PMID: 17950041.

7. Flanders AE. Medical image and data sharing: are we there yet? Radiographics 2009;29(5):1247-1251. PMID: 19755594.

8. HealthIT.gov. State health information exchange cooperative agreement program [Internet]. Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. cited at 2017 Oct 1. Available from: https://www.healthit.gov/policy-researchers-implementers/state-health-information-exchange

9. Health Information and Quality Authority. Overview of healthcare interoperability standards. Dublin: Health Information and Quality Authority; 2013.

10. Seroussi B, Bouaud J. Adoption of a nationwide shared medical record in France: Lessons learnt after 5 years of deployment. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2017;2016:1100-1109. PMID: 28269907.

11. Latham & Watkins Internet & Digital Media Industry Group. French digital republic law expands rights of users and regulators (Law No. 2016-321 of 7 October 2016). Los Angeles (CA): Latham & Watkins; 2016.

12. Bowd R. Development and evaluation of a program to improve clinician and patient communication during a telehealth consultation: CRISP Telehealth [dissertation]. Brisbane: School of Nursing; Institute of Health and Biomedical Innovation; Queensland University of Technology; 2012.

13. PricewaterhouseCoopers. Australia introduces mandatory data breach notification regime [Internet]. London: PricewaterhouseCoopers; 2017. [cited at 2017 Oct 1. Available from: http://www.pwc.com.au/legal/assets/legaltalk/privacy-amendment-notifiable-data-breachesbill-2016.pdf

14. Lee M, Heo E, Lim H, Lee JY, Weon S, Chae H, et al. Developing a common health information exchange platform to implement a nationwide health information network in South Korea. Healthc Inform Res 2015;21(1):21-29. PMID: 25705554.

15. Moghaddasi H, Rabiei R, Asadi F, Ostvan N. Evaluation of nursing information systems: Application of usability aspects in the development of systems. Healthc Inform Res 2017;23(2):101-108. PMID: 28523208.

17. Hussain A, Rivers P, Stewart L, Munchus G. Health information exchange: current challenges and impediments to implementing national health information infrastructure. J Health Care Finance 2015;42(1):1-8.

18. Luna D, Almerares A, Mayan JC, Gonzalez Bernaldo de Quiros F, Otero C. Health informatics in developing countries: going beyond pilot practices to sustainable implementations: a review of the current challenges. Healthc Inform Res 2014;20(1):3-10. PMID: 24627813.

Figure 1

Health information exchange (HIE) system architecture for exchange between hospitals and clinics. The HIE center consists of an MPI server and a registry, and it is interchangeable between all institutions.

-

METRICS

- Related articles in Healthc Inform Res

-

Public Acceptance of a Health Information Exchange in Korea2018 October;24(4)

Recent Movement on Education and Training in Health Informatics2014 April;20(2)

Implementation of Medical Information Exchange System Based on EHR Standard2010 December;16(4)

Application of the HoQ Model to Operations of Health Information Websites2005 March;11(1)